23 Dec The New York Times : Why Volkswagen Is Building a Team of 3,000 Engineers in China

Media Source : The New York Times

Volkswagen is shifting more operations to China, tapping the country’s electric vehicle capacity and building factories.

By Keith Bradsher and Melissa Eddy

Keith Bradsher reported from Hefei, China, and Melissa Eddy from Berlin.

Volkswagen used to import shock absorbers from Central Europe for cars it makes at Chinese factories. Now it buys them from a company in China for 40 percent less.

After relying for decades on engineers in Germany to design cars for the Chinese market, Volkswagen has begun hiring for a team of nearly 3,000 Chinese engineers, which will include hundreds transferred from Volkswagen operations elsewhere in China. They will design electric cars at VW’s industrial complex in Hefei, a city in central China.

The new strategy, which Volkswagen calls “In China, for China,” is another sign of how China’s commanding lead in electric vehicles has upended global auto making. Chinese car brands are appearing more in Germany and throughout Europe, causing politicians to worry about job losses.

“We all know how difficult it is to make money on electric cars,” said Ralf Brandstätter, the chairman and chief executive of VW’s overall China operations.

“To increase our efficiency, we have to reduce our work force,” Oliver Blume, Volkswagen’s chief executive, told the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

The cuts in Europe and imports from China could produce a double whammy for Germany, where the car industry has been a mainstay of the economy and accounts for nearly 800,000 jobs. Industry analysts predict the shift to electric vehicles, which are simpler to assemble than gasoline-powered cars, will cause that number to shrink by 12 percent.

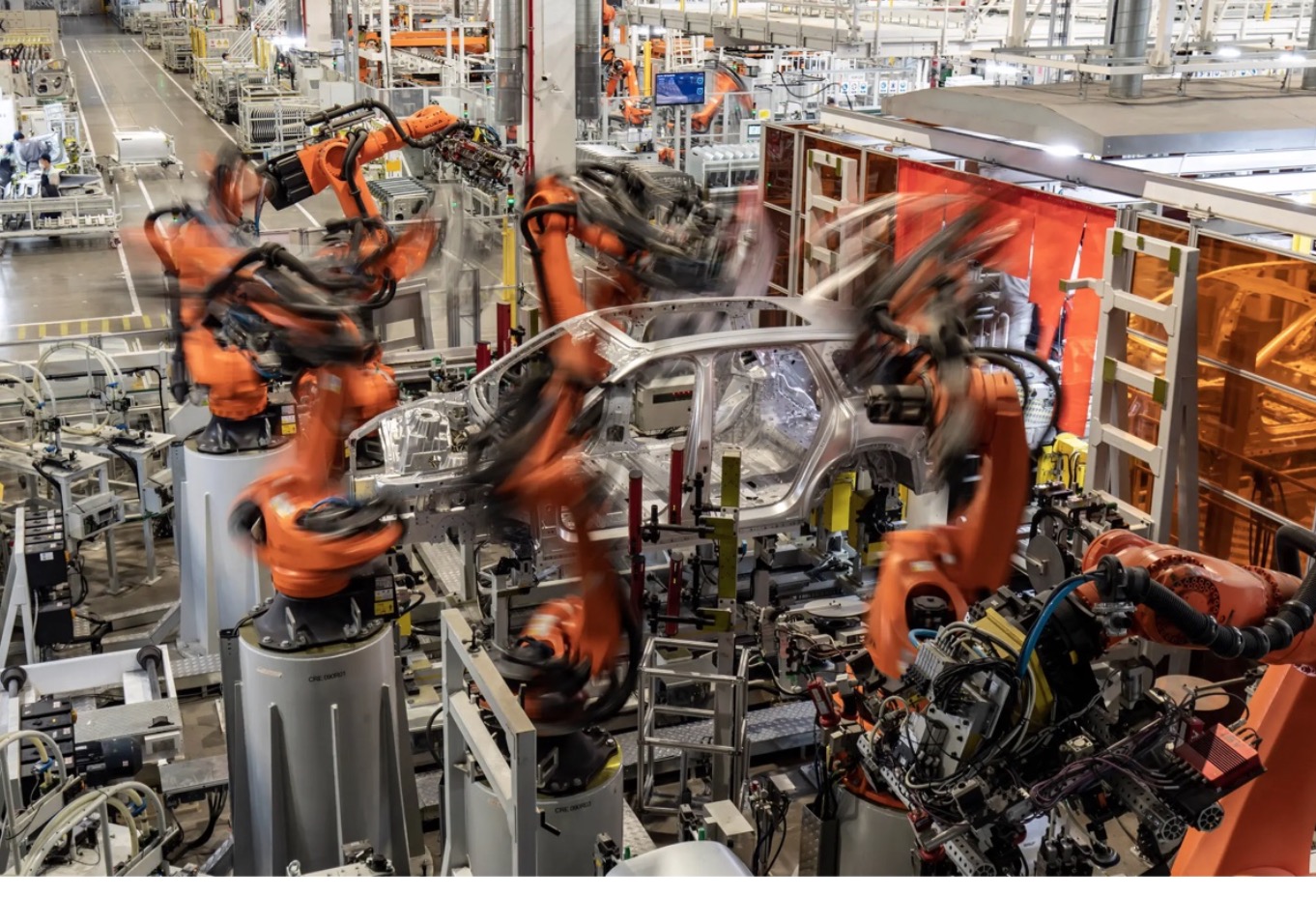

VW and Chinese carmakers have begun building facilities in China to make electric cars, instead of converting existing factories. The new factories, for local manufacturers like BYD and Nio as well as VW in Hefei, are among the world’s most modern and highly automated.

Midea, a Chinese appliance maker, in 2016 bought the German company Kuka, a leading producer of car factory robots. The new VW factory in Hefei uses robots from Kuka, which has shifted considerable production to Shanghai.

Volkswagen is the longtime leader for gasoline-powered cars in China, holding almost a fifth of the market through two big joint ventures with Chinese state-owned companies. But it sells less than 3 percent of the country’s electric cars.

VW is racing to catch up. Its new factory in Hefei is designed to churn out 350,000 cars a year initially, more than the industry standard size of 250,000 or so. And the buildings have been built with large expanses of empty space inside, so that further equipment can be quickly installed to ramp up production even higher.

Building a factory in China, instead of converting existing factories, has big advantages for Volkswagen. Starting in the 1980s when China began opening to foreign automotive investment, Beijing has required that foreign automakers assemble gasoline-powered cars in China through joint ventures with its state-owned automakers, and share management control. Volkswagen owns 40 percent of one of its joint ventures, with First Auto Works, and 50 percent of the other, with Shanghai Automotive.

But Beijing has exempted electric car production from the joint venture rule. Volkswagen owns 75 percent of its electric car manufacturing operation in Hefei — a local partner owns the rest — and VW fully owns its new engineering center in the city. It has full managerial control of both. Tesla, the leading foreign maker of electric cars in China, has operated in Shanghai since 2019 free of any joint venture requirement.

Foreign automakers are allowed full ownership of factories that make auto parts. So converting these to electric car component production has been more worthwhile.

Despite its aggressive new push in China, Volkswagen must compete with a domestic auto sector that receives heavy government assistance. Just 30 miles from its Hefei factory, a Chinese electric rival, Nio, has opened its second factory. Its operation is in some ways even more advanced than Volkswagen’s — sections of the assembly line are essentially mobile and can be rolled to new locations.

Nio’s two factories give it the capacity to assemble 600,000 cars a year, even though its annual rate of sales this autumn is only about 200,000 cars. Nio is nonetheless already building a third plant.

Volkswagen executives say that with China doing so much to build up its car industry, they have to be involved. “To build up a Chinese automotive industry,” Mr. Brandstätter said, “was a clear target always of the industrial policy of the government.”

Melissa Eddy is based in Berlin and reports on Germany’s politics, businesses and its economy. More about Melissa Eddy

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.