14 Nov Plugged In: BYD’s Wang Chuanfu Explains How China’s No. 1 EV Maker Caught Up With Tesla

Media Source : Forbes

Media Source : Forbes

09 NOV 2022

by Russell Flannery

This story appears in the November 2022 issue of Forbes Asia. Subscribe to Forbes Asia This story is part of Forbes’ coverage of China’s Richest 2022. See the full list here.

BYD’s Success Puts Him No. 11 On China’s 100 Richest With $17.7 Billion Fortune.

The Chinese billionaire whose BYD just usurped Tesla as the world’s biggest seller of electric cars has some advice for entrepreneurs. “Do more and talk less,” says Wang Chuanfu, chairman of BYD, China largest EV maker in an exclusive interview by email.

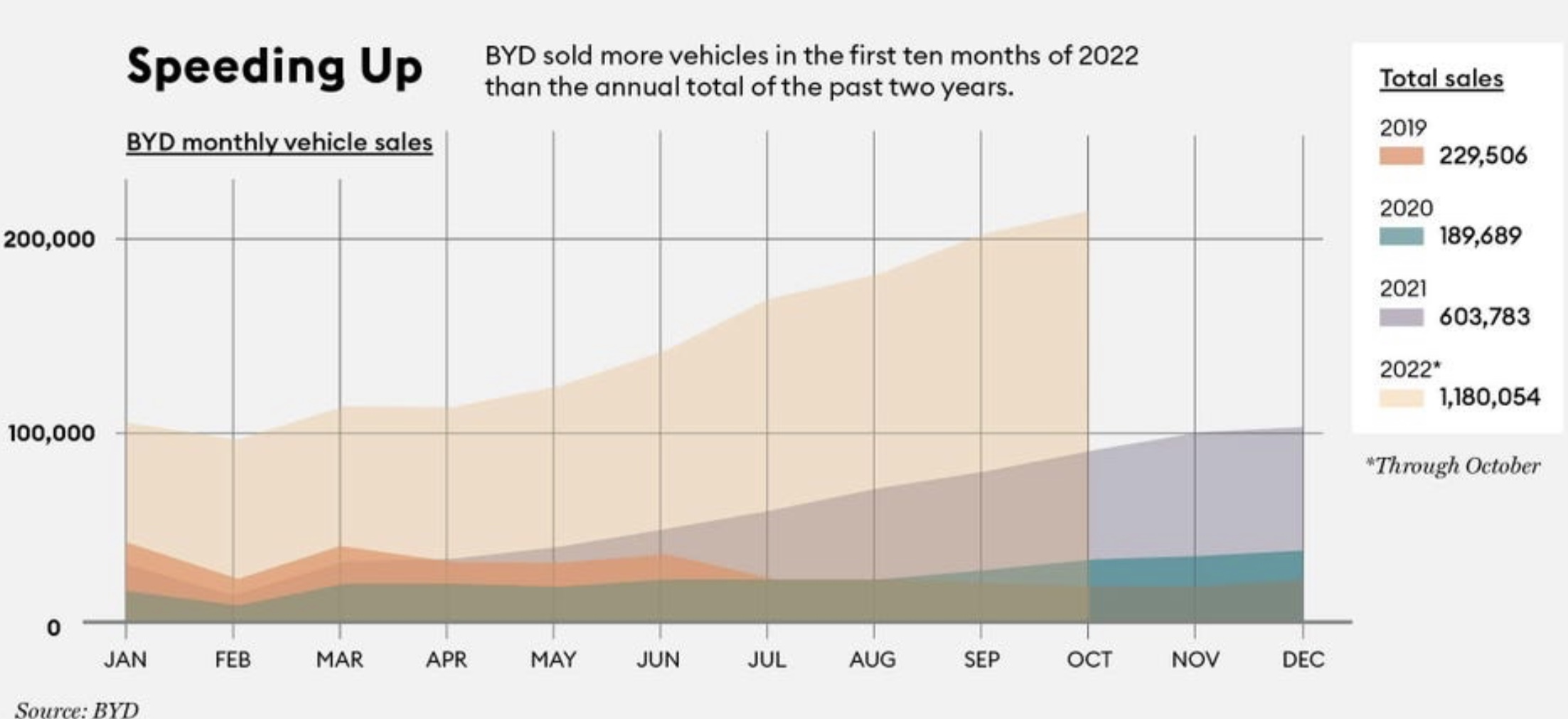

His Shenzhen-based company outpaced its U.S. rival in the first half of 2022, selling some 641,000 electric and hybrid plug-in models, versus Tesla’s 564,000. This marked a fourfold increase in BYD’s year-earlier sales, despite industry disruption from Covid-19 related lockdowns in Shanghai.

Behind its pole position is a portfolio of innovative tech, says Wang: “[BYD] has mastered the core technologies of the whole industrial chain of new energy vehicles, such as batteries, motors and electronic controls.”

That list also includes semiconductors—BYD’s chipmaking arm, BYD Semiconductor, specializes in making the chips used in EVs, which has allowed the firm to get around shortages that disrupted sales of other EV makers. In a global EV market projected to reach $824 billion by 2030 (at a CAGR of 18%), according to Portland-based Allied Market Research, “vertical integration is giving BYD long-term staying power while smaller rivals that aren’t yet vertically integrated will be driven out,” says Bill Russo, CEO of investment advisory firm Automobility in Shanghai.

In the first nine months of the year, BYD’s net profit nearly quadrupled to a record $1.3 billion year-on- year, fueled by new EV sales that soared 250% to 1.2 million over that period. Its market cap is around $100 billion, though short of Tesla, rivals the combined market values of U.S. incumbents Ford Motor and General Motors; and it’s given Wang a net worth of $17.7 billion and the No. 11 rank on China’s 100 Richest list. Besides Wang, BYD has generated two other billionaires. Wang’s cofounder and cousin Lu Xiangyang, a non-executive director at BYD, who ranks No. 18 with a fortune worth $12.7 billion, and director Xia Zuoquan, though he missed the minimum for the list.

“First, technology serves strategy, and secondly, it serves products,” says Wang. ASKA LIU/FORBES CHINA

Already a household name in China, where BYD makes up almost 70% of sales, Wang’s pursuing a more aggressive global push. In Asia, the 56-year-old recently launched new EV models in Japan, Thailand and India, and plans to build factories in the latter two to increase capacity. In October, BYD introduced three electric models at the Paris Auto Show, part of bigger plans for Europe. The company, which has over 30 production bases worldwide, said it expects to sell at least 1.5 million EVs this year, with a reported goal of 4 million in 2023

With know-how in hand, strategy becomes “the direction of enterprise success,” Wang says. “First, technology serves strategy, and secondly, it serves products. Technology can make enterprise strategy more precise, and it can also make enterprises look higher, farther and deeper.” The cost of the wrong strategy is often underestimated, he adds. “If a vehicle model breaks down, it may only cost several hundred million yuan, but if the strategic direction goes wrong, it may take three to five years, and time cannot be bought with money.” One combination of technology and strategy success at BYD has been the development of what it calls a blade battery, a cobalt-free alternative to other rechargeable lithium-ion batteries that are said to be safer and more stable. BYD not only installs the batteries in its own cars; it sells them to other automakers, reportedly including Tesla.

Another part of its strategy is to make models that are more affordable than its competitors. Chinese EV makers Nio and XPeng target the luxury market with cars with higher prices to match. The majority of BYD’s lineup sells for between $13,200 and $46,700. Meanwhile Tesla models started at around $50,000 before recent reported price cuts. BYD also has a depth of experience operating in the competitive China market, and made its first move overseas nearly a decade ago with an electric bus factory in California.

“They have had some tough customers which helped them build up thick skin and that book of lessons learned,” says Tu Le, founder of Sino Auto Insights, a consultancy that follows China’s auto industry.

Wang grew up in one of the country’s poorest provinces. He left his village home to get bachelor’s degree, and then a master’s, in battery technology, and worked as a vice supervisor at Beijing Nonferrous Research Institute. When he was in his 20s, Wang moved south to China entrepreneurial hotbed Shenzhen, and with cousin Xiangyang in 1995 started a mobile-phone battery maker called BYD—an acronym for “Build Your Dreams”—supplying the likes of Dell. He expanded to cars in 2003 with the purchase of a small firm called Tsinchuan Automobile.

But it was an investment from the Oracle of Omaha that really put BYD on the global investment map. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway in 2007 bought a 10% stake at HK$8 a share (now a roughly 7% stake worth more than $5 billion) as it looked to get in on growing demand for cars in China. Despite BYD’s success, Wang has kept a low profile, generally shunning the limelight.

Evolving customer demands in the EV market may favor China’s EV makers, especially BYD, which HSBC in a recent research note projected would see revenue triple to 699 billion yuan in 2024 from 216 billion yuan in 2021. Besides the growing market for EVs—at the end of 2021, there were 16.5 million electric cars on the road, a number expected to grow to 300 million by 2030, with EVs making up 60% of new car sales, the IEA says—the EV industry is shifting to a future where cars charge up like mobile phones. Chinese companies who already have jumped on the trend as a way to leapfrog over existing Western firms are now ahead of the pack, says Automobility’s Russo. China, the world’s largest EV maker and the largest auto market, also leads the world in making batteries that power EVs.

Wang emphasizes that one must disrupt your own technology before others do it for you. “To have the innovative consciousness of being the first, we need to constantly explore unknown fields and move forward firmly,” Wang says. And that process isn’t easy. “BYD devoted itself to studying new energy technologies, [overcame] bottlenecks, and encountered many difficulties,” he says. “Perseverance is an important part of entrepreneurship.”

That’s handy for bumps in the road. The company had to pause delivery of its BYD ATTO 3 in Australia over a child seat compliance issue in October. Meanwhile, BYD was among listed EV makers caught up in recent economic and political uncertainty. Their stocks plunged after President Xi Jinping gained an unprecedented third term during China’s 20th Party Congress (BYD shares have since recovered). Under Xi’s leadership, tech companies have faced tighter regulations, with further curbs expected.

Success in a rapidly changing industry means “flexible and efficient decision-making.” Wang says. “At present, the speed of market changes and technology iterations is getting faster and faster, and the response speed of enterprises to the market must keep up with the changes of the times. If enterprises make slow decisions, it will be difficult to succeed.”

Russell Flannery

I’m a senior editor and the Shanghai bureau chief of Forbes magazine. Now in my 21th year at Forbes, I compile the Forbes China Rich List. I was previously a correspondent for Bloomberg News in Taipei and Shanghai and for the Asian Wall Street Journal in Taipei. I’m a Massachusetts native, fluent Mandarin speaker, and hold degrees from the University of Vermont and the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.