06 Jul WIRED : The Rise and Precarious Reign of China’s Battery King

Media Source : WIRED

Zeng Yuqun is China’s most prolific battery billionaire. His ascent has major implications for a world increasingly reliant on electric vehicles.

PHOTOGRAPH: QILAI SHEN/BLOOMBERG/GETTY IMAGES

The headquarters of battery giant CATL tower over the coastal Chinese city of Ningde. To the untrained eye, the building resembles a huge slide rising out of the urban sprawl. It is, in fact, a giant monument to the company’s raison d’être: the lithium-ion battery pack.

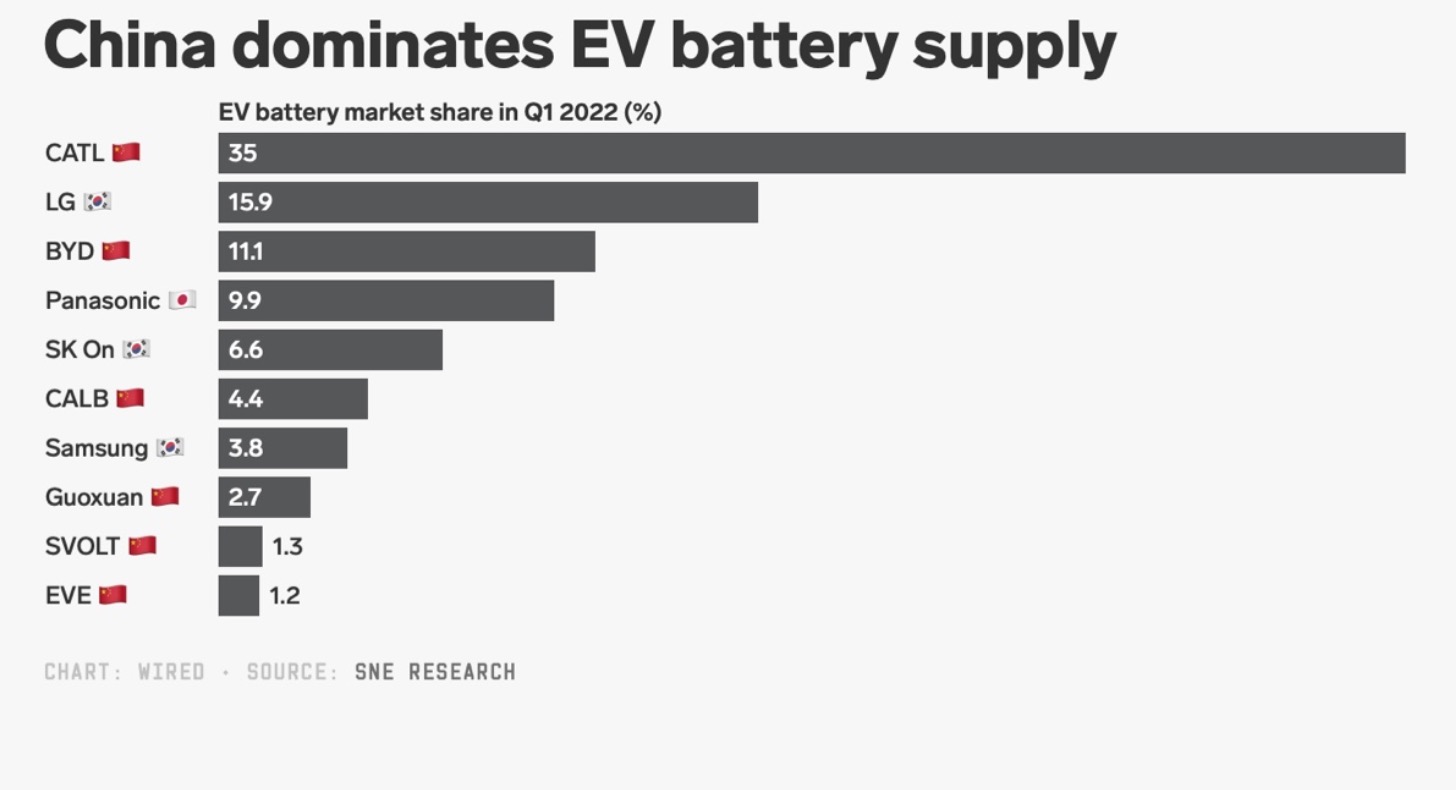

You may have never heard of CATL, but you’ve definitely heard of the brands that rely on its batteries. The company supplies more than 30 percent of the world’s EV batteries and counts Tesla, Kia and BMW amongst its clients. Its founder and chairman, 54-year-old Zeng Yuqun, also known as Robin Zeng, has rapidly emerged as the industry’s kingmaker. Insiders describe Zeng as savvy, direct, and even abrasive. Under his leadership, CATL’s valuation has ballooned to 1.2 trillion Chinese yuan ($179 billion), more than General Motors and Ford combined. Part of that fortune is built on owning stakes in mining projects in China, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Indonesia, giving CATL a tighter grip on an already strained global battery supply chain.

Such scale gives CATL huge influence—and allows the company to be picky with its contracts and push the rising prices of raw materials onto its clients. “They’re pretty much dictating the terms,” says Mark Greeven, professor of innovation and strategy at IMD Business School in Lausanne, Switzerland. CATL pushes clients for long-term, five-year deals. and it’s reluctant to customize its batteries for different carmakers, he adds.

So far, these decisions have helped make Zeng rich—very rich. He ranks 29th on Forbes’ 2022 list of the world’s wealthiest people. On Bloomberg’s 2021 list of the world’s top green billionaires, he is second only to Tesla CEO Elon Musk. Musk might make more headlines, but Zeng holds almost as much power.

But Zeng is not Musk. He dodges the limelight and rarely gives interviews. Insiders point out that Zeng is operating in an environment where notoriety could hinder, not help, his business. “In the West, the personality-cult style of leadership is something that’s valued, encouraged, and celebrated. In China, it’s dangerous,” says Bill Russo, former head of carmaker Chrysler’s northeast Asia business in Beijing who now runs the Shanghai-based advisory firm Automobility. “You can’t be bigger than Beijing.” Carmakers are also becoming wary of how much power CATL has as they search elsewhere for batteries to power their vehicles.

Zeng’s arrival on the EV battery scene can be traced back to 2010—and a meeting with Herbert Diess, who was purchasing manager for BMW at the time. Diess, who is now CEO of Volkswagen, had embarked on an international mission to persuade companies making mobile phone batteries to pivot to electric cars. He tried European companies, including Germany’s Bosch. But he also approached Zeng, who at the time was running a subsidiary of the Japanese electronics company TDK. Retelling the story in an internal meeting in May 2022, Diess described Zeng’s initial reaction as dismissive—it was, Zeng said, impossible for him to build such big batteries.

But, so the story goes, Diess’ plea for batteries stuck. In 2011, Zeng led a group of Chinese investors to acquire a 85 percent stake in TDK’s EV battery business, which they called CATL. BMW was its first key account. “Diess brought our company into the car battery business,” Zeng told Handelsblatt in 2020. “I am grateful to him for that.”

Diess might have inspired CATL to enter the EV market, but over the years Zeng earned a reputation as a founder who could master batteries as well as business. When he bought a US patent for mobile phone batteries in the early 2000s, he worked to improve the battery design himself, according to Lei Xing, former editor of Beijing-based media outlet China Auto Review. When BMW agreed to use CATL as its battery supplier, it was Zeng who read the 800 pages of requirements line by line, according to Yunfei Feng, a research associate at IMD Business School.

The attention Zeng paid to the technical details was crucial. When CATL started making car batteries, another Chinese company, BYD, was considered the market leader. But, as it grew, CATL made its technical supremacy pay. At the time, BYD used lithium iron phosphate batteries, while CATL used a combination of nickel, manganese, and cobalt, or NMC. “NMC had longer ranges,” says Xing. And when China rolled out EV subsidies in 2015, batteries with longer ranges received more support. “This benefited CATL tremendously,” Xing adds.

Subsidies were a crucial part of CATL’s success, and many analysts point to Beijing’s Made in China 2025 plan as key to the company’s evolution. The policy was designed to boost strategic high-tech sectors, including EVs. Between 2009 and 2021, around 100 billion yuan ($14.8 billion) in subsidies were handed to car buyers, according to an estimate by China Merchants Bank International. As a result, Chinese consumers received tax breaks for choosing EVs over combustion engines, but only if those EVs included batteries made with Chinese cells. That drove demand for CATL batteries not just among Chinese EV makers but also among international firms trying to tap into the lucrative Chinese market.

Buoyed by the subsidy, Zeng worked to raise money so the company could invest in its supply chain and pour cash into research and development. Between 2015 and 2017, CATL raised over $2 billion in equity financing before going public in June 2018, according to Kevin Shang, research analyst at Wood Mackenzie’s global energy storage team. “They were able to invest in the whole supply chain, from mining to materials manufacturing to the battery cells making and even to recycling.”

And as CATL grows, the company is expanding beyond China. Its first plant outside its home country is expected to open in the central German state of Thuringia later this year. In anticipation, Zeng has made himself accessible to the German car industry. “If you write him an email, he will answer very fast,” says Ferdinand Dudenhöffer, director of Germany’s Center for Automotive Research, a research institute that produces reports for the country’s carmakers. Dudenhöffer met Zeng at the Frankfurt Auto Show three years ago, where the CATL founder complained to him about the lack of government subsidies his firm was receiving in Germany. CATL decided to set up in Germany before EU subsidies for battery manufacturers had been finalized, meaning the company couldn’t apply for support, says Dudenhöffer. “He very quickly picked up on the problems.”

Germany, which produces more cars than any other European country, was quick to realize the importance of collaborating with Chinese firms, says Dudenhöffer. “The industry knows China is very important,” he says. “If you don’t stay in contact, do business and joint research with Chinese companies, you will not be in a leading position.” But elsewhere, the automotive industry is growing wary of CATL’s influence.

The global shortage of semiconductors has made car firms hyper-aware of supply chain bottlenecks. That’s pushing them to strike deals with CATL’s competitors or to try to build out their own battery plants— a trend that is worrying Zeng’s investors. CATL’s stock dropped 7 percent after competitor BYD said it would supply batteries to Tesla “very soon.” General Motors, another CATL client, is planning a new US battery plant in partnership with South Korea’s LG Energy Solution. Toyota is planning to open its own battery plant in North Carolina, and Ford is building twin battery plants in Kentucky.

“The policy of the automotive industry for a long time has been that they never single-source, because that gives too much power in the relationship to the supplier,” Russo says. “What does that mean for the likes of CATL? It means you’re going to have more competition.” CATL’s take-it-or-leave-it attitude is also pushing carmakers to consider working with smaller companies, who might have less experience but are more willing to customize their products, Greeven adds.

But weaning the industry off its reliance on CATL won’t be easy. Carmakers will find it difficult to manufacture high-quality batteries at a low enough cost, especially without CATL’s scale and expertise, says Shang.

Squeezed by an industry concerned by its position of power, CATL has doubled the number of its R&D employees between 2020 and 2021 to more than 10,000 people. It has also been securing new lithium supplies, spending $130 million in April on a mine in southern China. At the same time, the company has created new products to address existing industry problems, declaring plans in July 2021 to start producing sodium-ion batteries. Such breakthroughs could be crucial—sodium is the sixth-most-common element on earth, and batteries that use it would ease the car industry’s reliance on lithium, which could face major shortages as early as this year.

But it might not be the global car industry that ends Zeng’s rise—but China itself. His ascent coincides with an uneasy time for Chinese billionaires, with last year’s tech crackdown wiping billions off some of the country’s most profitable companies. The Chinese government had accused the technology industry of fueling wider inequality in the country, and Alibaba cofounder Jack Ma became the face of the crackdown. The billionaire, who had his own TV show called Africa’s Business Heroes and starred in his own action movie, fell from grace after giving a speech that criticized Chinese regulators for stifling innovation. Alibaba’s IPO was swiftly canceled and it received a record $2.8 billion antitrust fine. Around $10 billion has been wiped off Ma’s wealth since this time last year, according to Bloomberg’s billionaire index, as his fortune tracks Alibaba’s slide in value since the crackdown.

The move against Ma can be partly attributed to China’s “common prosperity” drive—an effort to reduce the gap between rich and poor—which president Xi Jinping has described as one of the country’s most important goals over the next 15 years. Although the pressure on tech has eased since last year, the push for common prosperity has continued. In June, banks in China were told to rein in executive pay. Ma’s downfall points to how the Chinese Community Party’s pursuit of “common prosperity” could affect Chinese billionaires, who also represent an alternative power base to Beijing.

As the most successful of China’s growing cadre of EV billionaires, that puts Zeng at risk of becoming a target. “Zeng is richer than Jack Ma, but he is definitely not as noisy,” says Greeven. Despite that, CATL has already faced a soft rebuke for its behavior. In November 2021, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange raised concerns about CATL financing “excessively.” A crackdown on the electric vehicle and battery industries in China could have a profound impact on an industry the whole world is relying on for the green transition. China produced 44 percent of the world’s EVs in the last decade and around 80 percent of the world’s lithium-ion batteries. In the short term, that share is projected to rise.

Concerns have been raised that Beijing would rather replace CATL and other battery giants with a network of small and medium-size businesses. But experts are divided on how much risk CATL is facing. “What Jack Ma does versus what Robin Zeng does, it’s completely different,” says Xing. But Russo believes CATL’s risk depends on whether Zeng can continue to balance his government relationships with his public persona.

CATL may have been crucial in helping China develop its EV supremacy, but the recent tech crackdown provides a warning that Beijing can abruptly reorganize its industries if they start to clash with wider political ambitions. There are already hints of how that might play out. In 2015, businesses controlled by a state-owned aerospace company and a district government cofounded CALB, a state-operated firm which also specializes in lithium-ion battery production. Such a move could pit CATL against the Chinese state itself.

The two firms have already clashed, with CATL accusing CALB of patent infringement and seeking damages of 518 million yuan ($77.4 million). And the legal dispute is intensifying just as CALB prepares to list on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange later this year. In its IPO prospectus, CALB describes itself as China’s second-largest EV battery company and seventh in the world. But with a state-owned company now vying for control of China’s battery production industry, it’s no sure thing that will remain the case. “Too much dominance is a bottleneck,” says Russo. “And that’s something that neither industry nor government would want.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.