26 Jun POLITICO : Europe gives China a taste of its own trade medicine

Media Source : POLITICO

Europe is using the threat of tariffs to press Chinese electric car makers to set up in the EU and share know-how.

JUNE 18, 2024 4:23 PM CET

BY JAKOB HANKE VELA AND JORDYN DAHL

In a remarkable turn of events, however, the EU is now considering a next step that invites China’s electric vehicle (EV) makers inside the walls.

The big idea is to use the tariff threat to force Chinese carmakers to come to Europe to form joint ventures and share technology with their EU counterparts, according to conversations with four diplomats and two senior officials.

There are signs the formula is already attractive with EU carmakers. Franco-American-Italian carmaker Stellantis has formed a joint venture with China’s Leapmotor to start Europe operations in September. Spain’s EBRO-EV has teamed up with Chery — China’s fifth-largest automotive company — to develop EVs in Barcelona.

“Joint ventures make sense, as a way to make sure that the Chinese don’t only set up final assembly plants in Europe, but also more substantial parts of the supply chain. Of course, it can also be a way to ask the Chinese to share some technology,” said one senior diplomat, who was granted anonymity to discuss the sensitive matter.

That’s astounding in two ways: First, it shows that the EU is gearing up to play the kind of more muscular, interventionist role in world trade that it used to accuse China of. But, more profoundly, it’s an admission China has not only caught up but already overtaken Europe in some sectors.

“This is a bit humbling for us, but we need to recognize that we are behind on certain technology,” said the first senior diplomat.

Falling behind

China caught up with European firms and then started surpassing them in terms of sales and technological prowess on everything from solar panels to consumer drones, and now EVs.

According to the German Chamber of Commerce in China, 69 percent of German automotive companies reckon their Chinese competitors already lead them in innovation or will do so within the next five years.

So, faced with the need to catch up, Europe’s tariff and joint venture plan is “an attempt to give China a taste of its own medicine,” said Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, director of the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE), a think tank.

Look what you made me do

In Germany, some of whose companies still make good profits in China and have the ear of the country’s politicians, the fear of a trade war prompted Chancellor Olaf Scholz to break ranks and openly question the EU’s electric vehicle subsidy probe.

Yet despite wide-ranging fears of the car tariffs in Berlin, the view among the majority of EU countries is that Brussels basically had no choice but to react to China’s massive subsidies across the entire EV supply chain, from raw material refining for batteries to finished cars.

“The Communist party last March … decided to increase industrial subsidies even more. They also decided not to stimulate domestic consumption and not to revalue the renminbi. If someone takes a decision like that, when there’s already so much capacity, it means: We want to flood you … it’s a declaration of a trade war,” said a third senior diplomat.

And the mood among the EU diplomats and officials that POLITICO spoke to was not one of Trumpian protectionist gloating about the decision to impose tariffs, but rather one of regret and alarm that this may well be a last resort — with European governments’ balance sheets so stretched they simply can’t match China’s subsidies.

Referring to the EU’s decision to impose anti-subsidy tariffs, Lee-Makiyama added: “It’s the Taylor Swift doctrine, where Brussels tells Beijing: ‘Look what you made me do.’”

If you can’t beat them, join them

Faced with massive pressure from Berlin to avoid a trade war, the joint venture plan to de-escalate the fight while securing some wins for Europe is quickly gaining traction in Brussels.

It may also be Europe’s last shot to play a bigger role in the EV supply chain.

Of course, political deals to secure big local investments are nothing new. “Every Asian carmaker had to invest in Europe in order to get tariff concessions. The Japanese built plants in France, Poland and Portugal. The South Koreans went into Central Europe. Also other Chinese firms like Huawei probably invested in France to gain partial access,” said ECIPE’s Lee-Makiyama.

What is new, however, is that the EU is not just using carrots such as subsidies and trade agreements, but also sticks such as the tariffs to encourage Chinese companies to invest on its soil.

Even more remarkable are discussions among officials and diplomats to use tools such as the investment screening regulation to cajole Chinese companies into such joint ventures.

“It’s for the Commission to come up with a proposal on that,” said the first senior diplomat when asked whether the EU would go as far as formally imposing local ownership requirements.

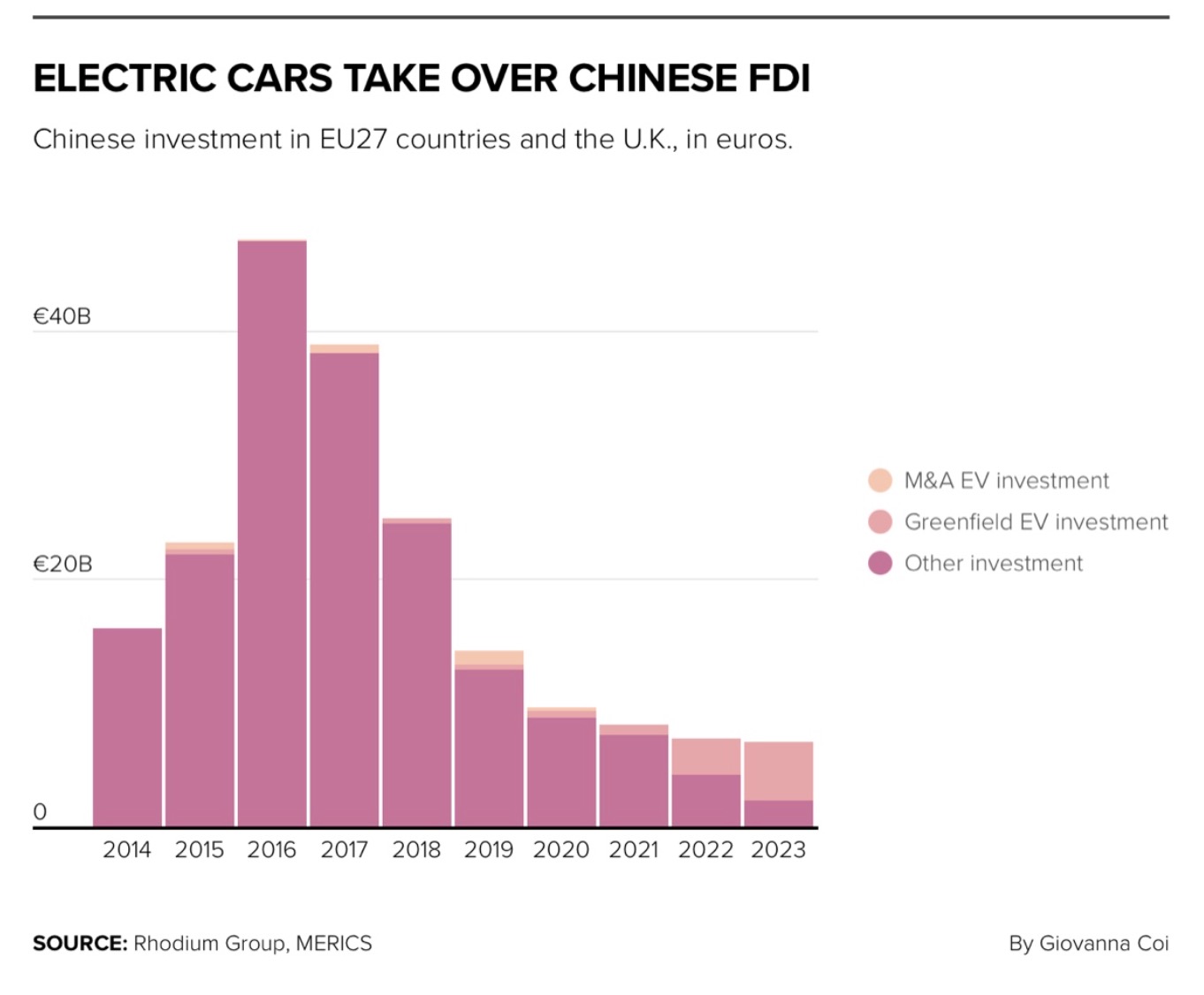

Hungary — now the top recipient of Chinese EV investment into Europe — also wants to make a push for such joint venture requirements in its upcoming presidency of the Council of the EU, said a fourth diplomat, suggesting there could be a deal to remove the EU’s tariffs on those Chinese carmakers that invest locally.

Industrial reality

In fact, EU policymakers may not have much of a choice, as the industry is already moving ahead with such joint ventures. After being forced into agreements to gain access to China’s lucrative market in the 1990s, many European car brands have come around to the idea and are signing on to new ventures to produce Chinese cars in Europe of their own accord.

“It’s a very natural development,” said Jens Eskelund, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. “European companies have been very successful in China … Europe needs to consider: What are the conditions under which Chinese investment can actually be a positive for Europe?”

Not everyone is eager to join hands and sing kumbaya, though.

More Chinese investments in Europe could follow soon, however. France is keen to attract Chinese battery- and carmakers. “BYD is welcome in France and China’s automotive industry is welcome in France,” Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire said last month.

CORRECTION: This story has been amended to correct details of the Stellantis JV and François Godement’s affiliation.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.