17 Oct The New York Times : China’s Economic Stake in the Middle East: Its Thirst for Oil

Media Source : The New York Times

11 OCTOBER 2023

China is the largest oil importer by far from Saudi Arabia and from Iran, highlighting the risk it faces if the war in Israel and Gaza were to broaden.

Reporting from Beijing

One big reason: oil.

No country buys more oil from Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-largest producer behind the United States. Half of China’s oil imports, and a little more than a third of all the oil burned in China, comes from the Persian Gulf, according to Andon Pavlov, the lead refining and oil products analyst at Kpler, an analysis firm in Vienna.

China has also started buying more oil from Iran, a longtime backer of Hamas, the group behind the attack. China has more than tripled its imports of Iranian oil in the past two years and bought 87 percent of Iran’s oil exports last month, according to Kpler, which specializes in tracking Iran’s oil exports.

China, the world’s second-largest economy, has become addicted to foreign oil at a stunning pace. As recently as the early 1990s, China was self-sufficient in oil. Now it depends on imports for about 72 percent of its oil needs.

By comparison, the United States’ reliance on imported oil peaked at about 60 percent around 2005, before the fracking boom transformed the United States into a net exporter.

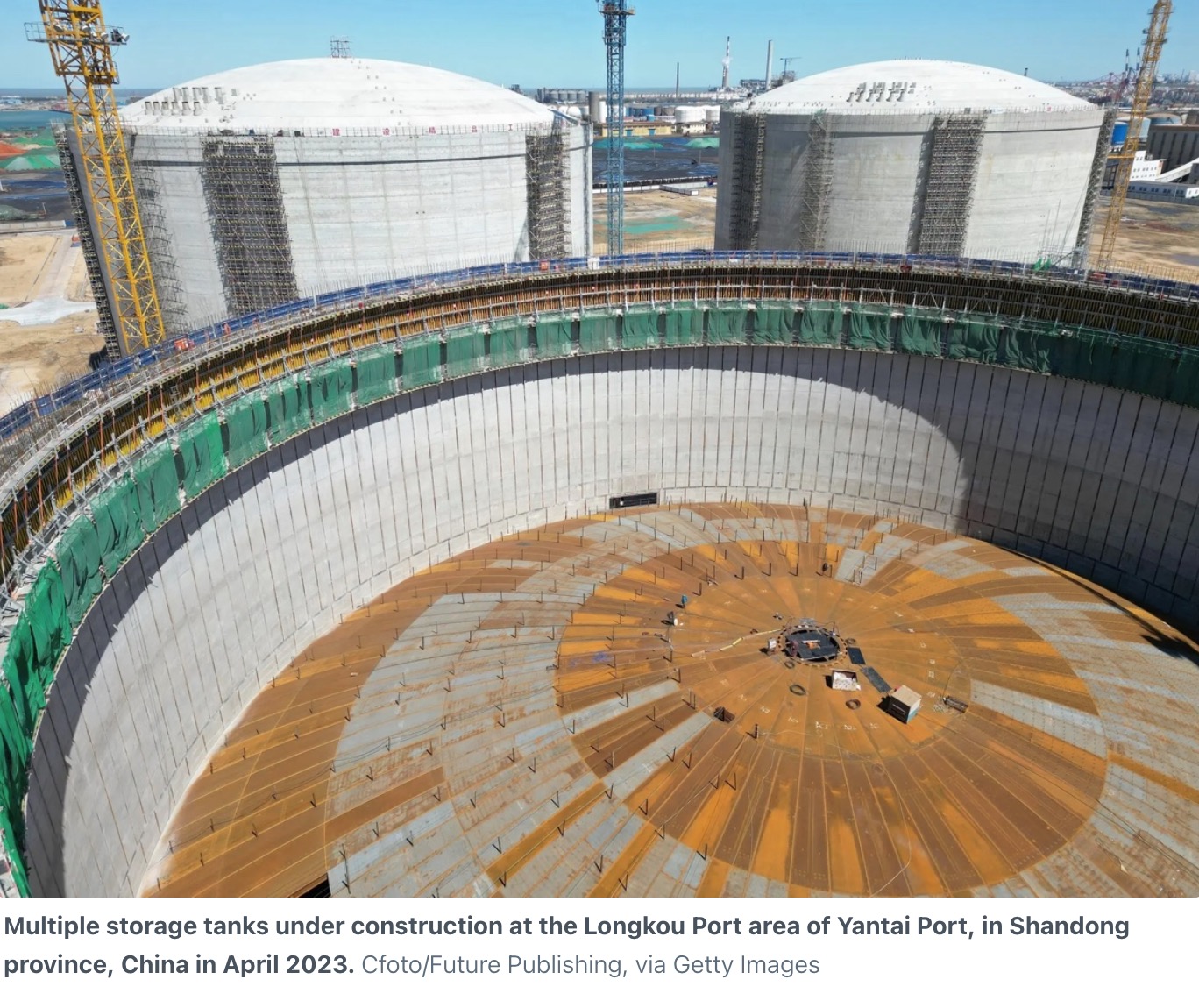

Xi Jinping, China’s top leader, has kept energy security as one of the country’s top priorities through his decade in office.

“Energy supply and security are crucial for national development and people’s livelihoods, and are a most important matter for the country that cannot be ignored at any moment,” Mr. Xi said in July.

But gasoline consumption has stayed high, as new car sales gradually change the overall fleet of mostly gasoline-fueled vehicles on China’s roads. Driving has also surged this year, including during a weeklong national holiday this month, because China ended nearly three years of “zero Covid” measures that restricted travel.

China does not officially acknowledge buying any oil from Iran, which is under broad international sanctions as it attempts to build nuclear weapons. But its purchases have been well documented by industry experts.

Iran relies on shipping oil aboard tankers that turn off their automatic location transponders, sometimes for weeks at a time, and often don’t turn them on again until they reach high-traffic waterways like the Strait of Malacca next to Malaysia.

China’s official statistics instead show Malaysia as one of China’s largest suppliers of oil, even though Malaysia has limited and shrinking oil production from aging oil fields.

Refineries in China that turn crude into gasoline and other products have shifted to buying more oil from Iran because Iranian oil is now cheaper than Russian oil, Mr. Pavlov said. Iranian oil sells at a discount to world prices of about $10 a barrel, despite sanctions, while Russian oil sells at a discount of about $5 a barrel, despite sanctions, he said.

“China always goes with what is cheapest,” he said.

“I’m highly skeptical of the pipeline’s commercial logic, but energy security and geopolitics might ultimately trump economics,” said Joe Webster, a senior fellow at the Global Energy Center of the Atlantic Council, a Washington research group.

“Since America doesn’t import much oil from that part of the world, the countries in that part of the world start to think how their geopolitical alliances will be reshaped in the decades to come,” said Kevin Tu, a Beijing energy consultant. “China has become a major stakeholder in this region whether it likes it or not, and China needs to play a role to stabilize the region in the years to come.”

Li You contributed research.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.