16 Jan THE WIRE CHINA : China’s EV Evolution

Media Source : The Wire China

By ELIOT CHEN — JANUARY 16, 2022

COVER PHOTO: The SAIC-GM-Wuling Mini EV, China’s best selling electric vehicle in 2021. Starting at $4,500, the Mini is a hit among young people who customize it with exotic decals.

China’s appetite for electric vehicles (EVs) has shifted into high gear, with homegrown companies moving to the fore. EV sales nationwide increased by roughly 150 percent to more than 3 million last year, according to figures from the Chinese Association of Automobile Manufacturers, and they are expected to double again in 2022, predicts the China Passenger Car Association.

The EV boom has given China’s auto industry a much-needed burst of speed, with sales of all passenger cars rising last year for the first time since 2017 — despite another drop in the sale of cars powered by internal combustion engines.

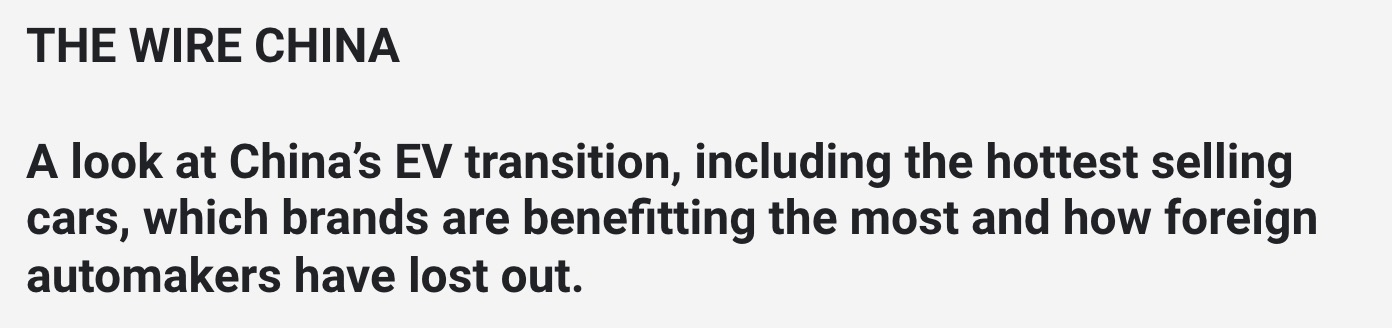

As China’s transition to electric vehicles motors ahead, local automakers have been the main beneficiaries. Eight of the top ten electric car models sold in China in 2021 were produced by Chinese carmakers, with foreign brands like Audi, GM, and Volkswagen — dominant for decades in China — lagging behind.

This week, The Wire looks at China’s EV transition, including the hottest selling cars, which brands are benefitting the most and how foreign automakers have lost out.

NO FRILLS, HIGH SALES

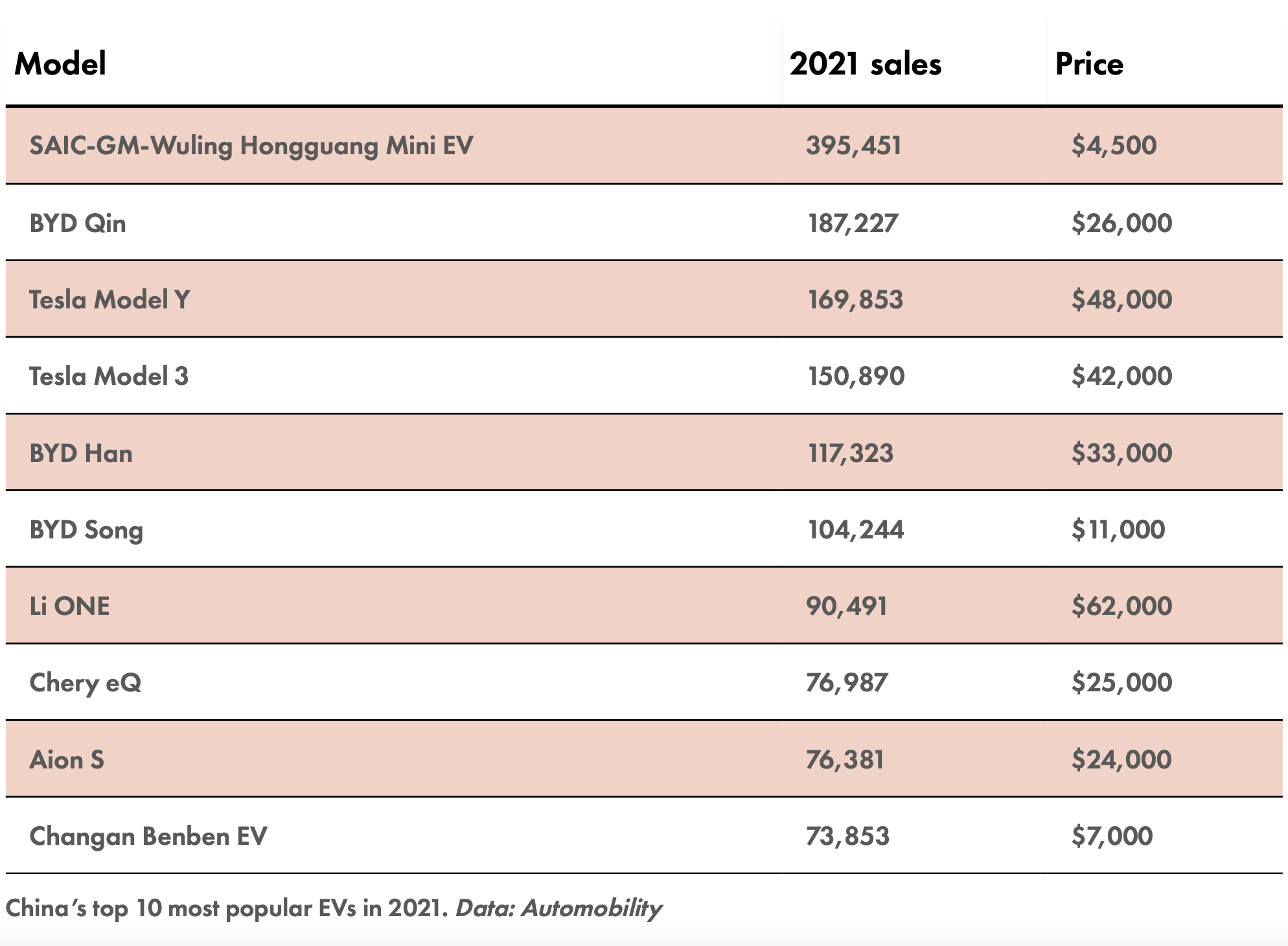

When Tesla declared plans to build a factory in China in 2019, the authorities showered Elon Musk’s venture with cheap land and ample subsidies. But for all the hype, Tesla’s cars are not China’s most popular EVs. Instead, China’s hottest electric car last year came from a brand unknown to most outside the country: the SAIC-GM- Wuling (SGMW) Hongguang Mini.

The Wuling Mini is as no-frills as it gets — early versions didn’t even have airbags. “Plastic quality… is somewhere between an economy car and a public bathroom,” scoffs one online reviewer. But the boxy microcar, which seats four passengers despite being less than ten feet long, starts at a mere $4,500 and can travel up to 100 miles on a single charge — ample range for a young city driver looking to upgrade from a motorcycle to a car.

“The people at Wuling came up with this idea that we’re going to market [the Mini] as an accessory,” says Michael Dunne, a longtime Asian auto industry consultant and CEO of ZoZo Go. “And people in third and fourth tier cities can buy this fun, cute, cool vehicle… and they hit a chord with those buyers.”

SGMW, a joint venture between state-owned enterprise SAIC, Liuzhou Wuling Motors and America’s General Motors, sold close to 380,000 Wuling Minis last year. (For comparison, sales of all EV models in the U.S. last year totaled about 430,000.) In second place was BYD’s Qin, while Tesla’s Model Y and Model 3 came in third and fourth, respectively. The remaining vehicles in the top ten were all Chinese.

AIM FOR THE MASSES

Several factors are driving China’s booming demand for EVs. The looming termination of government subsidies for new EV purchases at the end of this year may be encouraging some buyers to make their moves now. The government has been drawing down the subsidies by 10 percent every year since 2020, but they can still be worth as much as $1,200 per purchase.

But some industry observers argue that China’s EV market is past the point of relying on subsidies. “With subsidies, of course everybody will take the free candy, but it’s not the driving force behind this,” says Zozo Go’s Dunne. He argues that a broader pivot in consumer preferences, catalyzed by Tesla’s entry into the market, created genuine demand for EVs.

“Prior to 2020, electric vehicles were sold mostly to government agencies, taxi fleets, enterprises… and those sales were driven mainly by subsidies,” he says. “Then in 2020 we see Tesla begin to produce the Model 3, and it was almost a miraculous pivot. We witnessed a marketplace where overnight, EVs are cool and desirable, and that’s why they’re trending.”

A focus on mass market production is also giving local EV makers a big lead over foreign competitors. By rolling out cheaper models, brands like Wuling and BYD have tapped into a population of young, cost-conscious buyers who also tend to be early adopters of new technologies, while older, wealthier customers continue to favor foreign brands.

“Legacy automakers start from the assumption that I’m going to scale a new technology and it’s going to the showroom alongside traditional [internal combustion engines]… So they make the implicit assumption that you need to price the new tech at a price point above the incumbent,” says Bill Russo, founder of Automobility, a Shanghai-based consulting firm.

“The EV companies in China don’t think that way. They don’t even have an incumbent in many cases. So if you’re going to compete with Chinese companies, you need to ask, ‘What am I going to do to localize,’ otherwise you’re going to cede the market to them.”

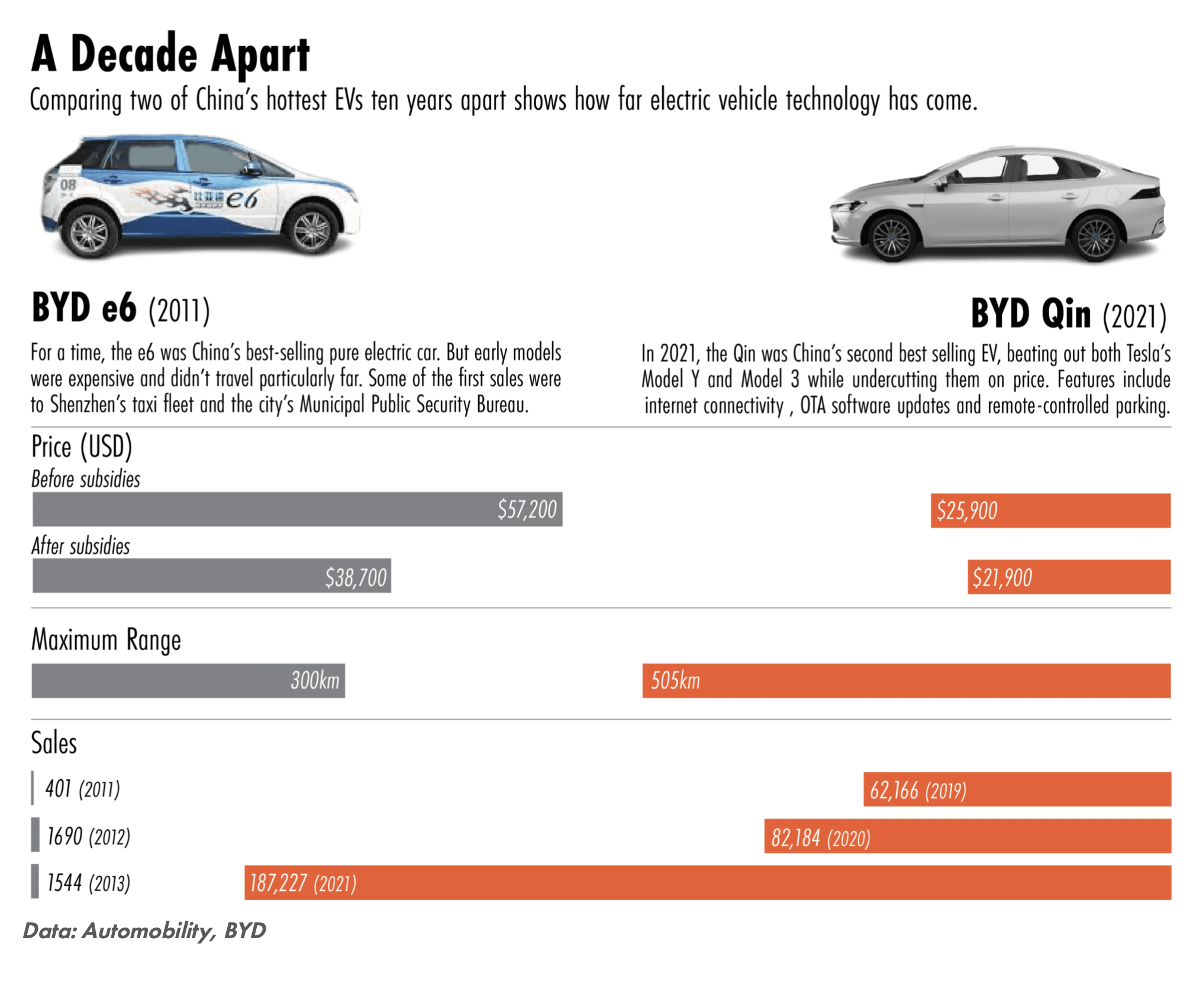

Chinese carmakers have one more trick up their sleeve: partnerships with domestic tech giants. Taking a page out of Tesla’s playbook, so-called “smart EV” manufacturers like Nio and Xpeng are partnering with companies like Alibaba and Baidu to introduce autonomous driving and connected car technology. These partnerships have also helped EV automakers secure vital semiconductor supplies amid a global shortage, according to Automobility’s Russo.

“Everybody can whine about not getting enough chip supply, but that’s true for everyone… Why are the [Chinese] EV companies growing while traditional auto companies are saying ‘I’m 10 percent down because of chip supply?’” Russo says. “Last I checked the EVs have chips in them too. The difference is they have supply chain relevancy to the electronics sector.”

Positioning themselves as tech companies first and carmakers second has boosted the stock prices of companies like Nio and Xpeng — like Tesla, the “smart EV” makers have drawn valuations far higher than traditional automakers, despite having relatively low vehicle outputs.

INFRASTRUCTURE

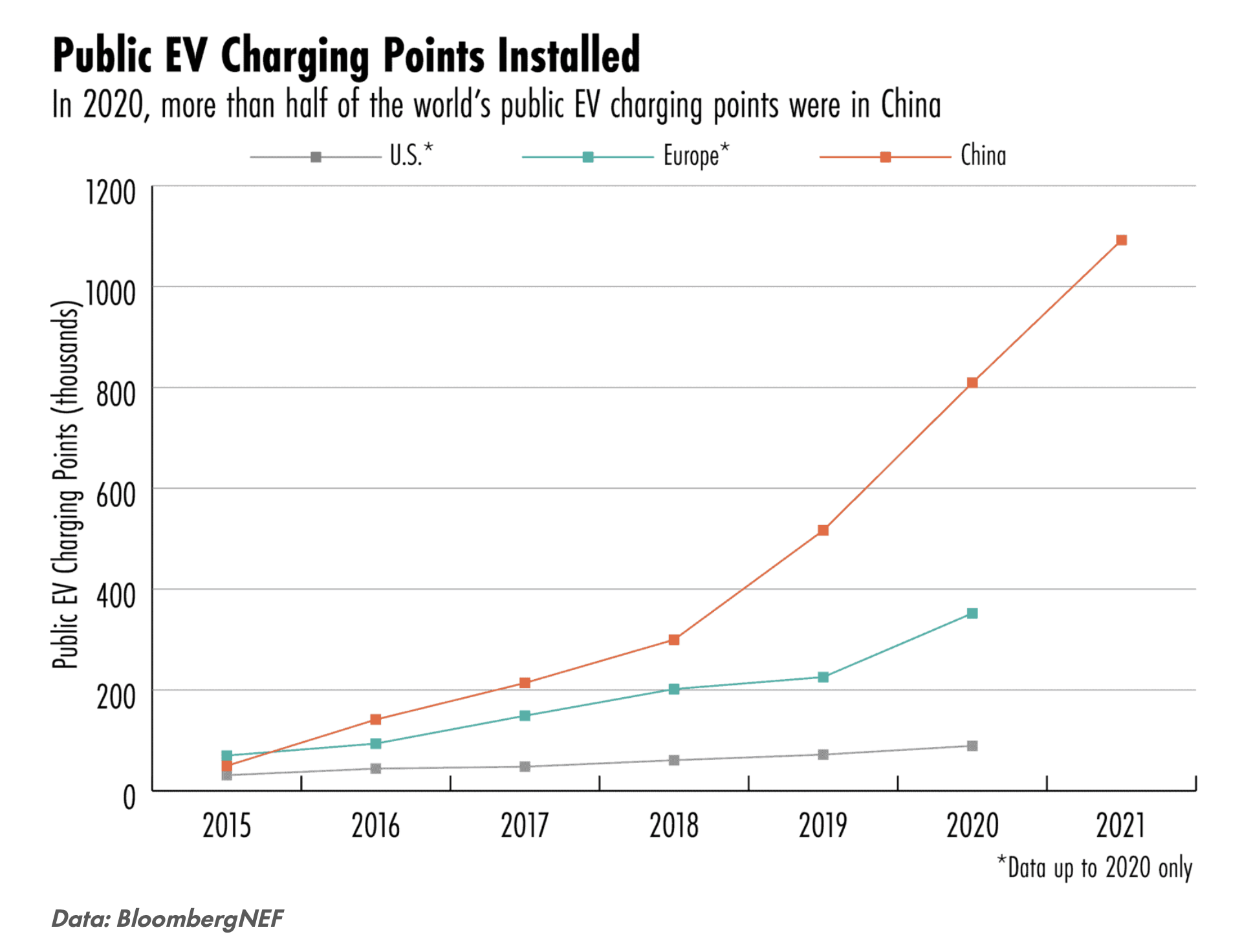

China’s EV boom wouldn’t go far without supporting infrastructure. The Chinese government has invested heavily on this front, more than doubling the size of the country’s charging network between 2020 and 2021 to 2.2 million stations, according to the Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Promotion Alliance.

“The government has been investing in charging points for the better part of ten years now,” says Dunne. “But really, the turning point is when companies themselves… began to build their own networks of superchargers, swap stations, and battery leasing options.”

By comparison, the U.S. has just 111,000 stations, less than half the number China added in 2021 alone. The Biden Administration’s $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill includes funding to install half a million new EV chargers in the next half decade.

Here’s how China and the U.S.’s public charging networks compare:

SOURCE: https://www.thewirechina.com/2022/01/16/chinas-ev-evolution/

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.