06 Nov The Role of Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles in Achieving China’s Carbon Neutral Vision

Courtesy of FCVC 2021 6th International Hydrogen Vehicle Fuel Cell Congress

By Bill Russo, Emily Wang and Maggie Zhou

China has recently struggled with severe power shortages, leaving millions of homes and businesses without power. The outages have rippled across eastern and central regions, where most of China’s population is concentrated. Over 20 provinces are facing energy rationing, creating uncertainties for business.

The power cuts are an outgrowth of a recent surge in energy use and a resultant shortage of coal. The rise in energy demand was caused by strong post-COVID recovery of the domestic economy and a surge in exports. China relies on coal to generate up to 70% of the country’s electricity. This year, China’s coal supply has fallen as domestic coal mining was restricted in a national effort to reduce carbon emissions, combined with import restrictions on Australian coal.

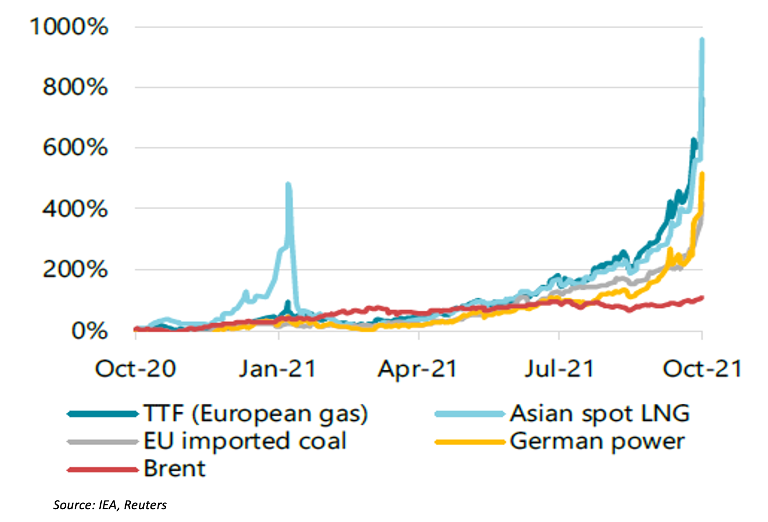

The energy shortage is not limited to China. Energy price shocks (see Figure 1) have hit major economies, especially in Europe and Asia, including UK, Germany, France, Japan, China, as well as Brazil. The situation has laid bare the fragility of global energy supply chains as countries pivot from fossil fuel to clean energy.

Figure 1. Evolution of Energy Prices

Recent disruptions underscore the need for adjustment of the world’s power supply structure, especially for economies highly dependent on energy consumption to generate growth like China. Sustainable energy resources must play a larger role in the energy mix, which presents an opportunity for hydrogen. Renewable energy (i.e. solar and wind power) is typically highly dependent on weather and environmental changes, which creates uncertainty for such energy sources to be integrated with the power grid. As an energy carrier, Hydrogen offers a high potential solution to new energy storage and distribution systems. Hydrogen electrolysis can provide large-scale and long-term supply of storable energy from renewable resources. The large-scale use of hydrogen for energy storage can contribute to the safe and stable operation of the power grid.

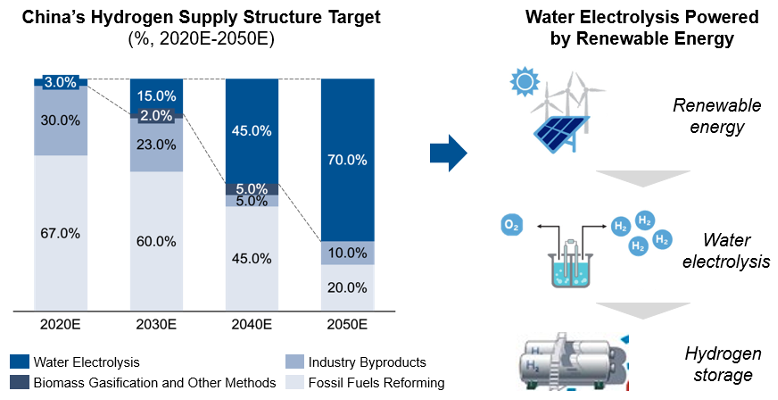

Hydrogen production from electrolytic water, also called green hydrogen, is expected to become a mainstream application in China because of its low carbon footprint, high purity, and easy integration with renewable energy sources (see Figure 2).

Source: 2020 China Hydrogen & Fuel Cell Industry White Paper, desktop research, Automobility analysis

Figure 2. Hydrogen Supply Structure in China

Hydrogen energy’s strategic importance to China’s 2060 vision

China initiated New Energy Vehicle (NEV) subsidies in 2009 to encourage the development of domestic industries around Battery Electric Vehicles (BEV), Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEV) and Fuel Cell Electic Vehicles (FCEV). In 2015, China set goals to commercialize Hydrogen energy and FCEV as a part of its “Made in China 2025“ policy, followed by the issue of “The 13th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of PRC“ in 2016, further defining hydrogen’s future role in China‘s energy supply chain.

In 2019, hydrogen energy was included for the first time into the Government Work Report, emphasizing the need to popularize hydrogen refueling station (HRS) infrastructure. During the 13th Five-Year Plan period, China built a solid foundation for its NEV industry, with 4.4 million NEVs added to the car population and the emergence of domestic BEV champions like NIO, Xpeng, BYD, and many others. Also, during this period NEV government subsidies have gradually been phased out for BEV and PHEV as these technologies have gained market acceptance. However, FCEV subsidies have been increased, as this technology is still in an early stage and needs the support.

The 14th Five Year Plan issued in March 2021 named “Hydrogen Energy and Energy Storage“ as strategic emerging industries. Hydrogen energy can play a critical role in decarbonizing China’s heavy industries (i.e. steel making), transportation, construction supply and other sectors, which is required to to achieve China‘s 2060 carbon neutral target.

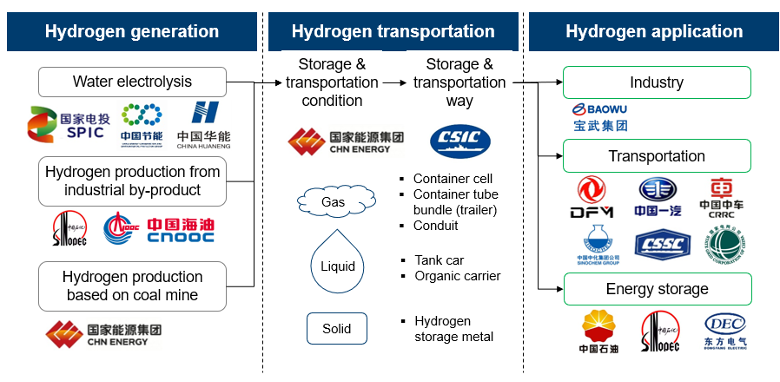

China’s central SOEs (state-owned enterprises under direct supervision of the central government) are highly involved with the hydrogen economy, 1/3 of which have made hydrogen related investments along the value chain of hydrogen production, distribution, and usage (see Figure 3). This is according to statistics from the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) of the State Council.

Source: Desktop Research, Automobility Analysis

Figure 3. Hydrogen Energy Value Chain

A new policy framework to drive China’s FCEV development

In contrast to China’s success in nurturing a globally competitive BEV industry, its FCEV market still in its infancy, despite a decade of generous government subsidies. In Sep. 2020, five Chinese state-level ministries and commissions jointly issued the “Notice on Deployment of FCEV Demonstration Projects”, signaling that purchase subsidies will be replaced by city cluster demonstration incentives from the central government level over the coming four-year policy period.

The notice specified a scheme for rewarding city clusters on technology and business innovations, cost reductions, scalable applications, and effective regulatory systems to drive the development at the local level. Three demonstration city clusters led by Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong have been announced. Local governments of the demonstration cities can allocate state rewards among local companies. Local governments of other cities have the authority to formulate their own FCEV stimulus policies sponsored by local fiscal revenue.

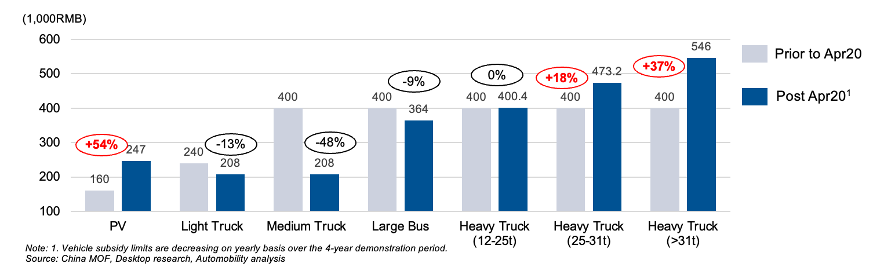

As can be seen in Figure 4, the city cluster subsidy scheme strongly favors heavy trucks and passenger vehicles. These subsidies target the development of entire FC industrial chain, especially for building a domestic supply chain. In the long run, new energy related applications such as green mines, green power plants, and green terminals will increase the utility of heavy duty trucks.

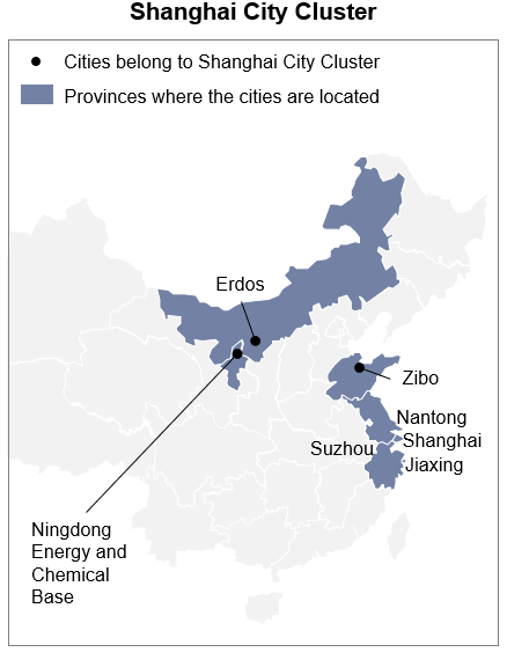

Figure 4. Upper Limit of Single Vehicle Subsidy Before vs. After City Cluster Policy

The Shanghai city cluster was the first approved demonstration project in August 2021. This cluster has the current capability of 3 million tons of hydrogen production per year, 16 hydrogen refueling stations, and over 1900 FCEVs in use, growing to a total of 5000 FCEVs over the four year demonstration period. This will include 3,400 trucks, 1,400 PVs and 200 buses. During this period, 73 hydrogen refueling stations will be built. The Shanghai cluster covers cities in eastern China region with strong FCEV value chain players, as well as the famous “coal city” Erdos (see Figure 5), which has 330,000 heavy trucks on road and has an urgent demand of emissions reduction.

Figure 5. Shanghai City Cluster FCEV Demonstration Zone

The path to commercialization of FCEV in China

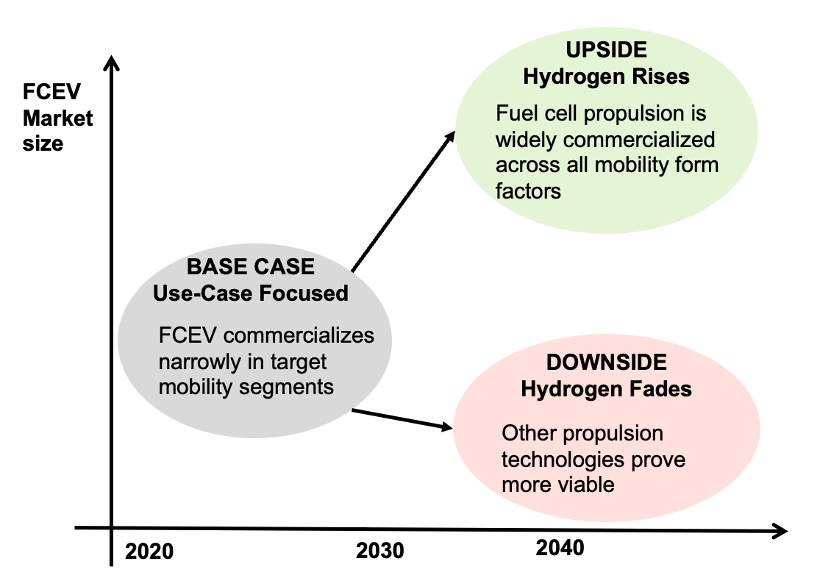

We believe the path to successful commercialization of FCEV in China is contingent on the success of these City Cluster FCEV Demonstration Zones. We expect there to be a Base Case scenario of Use-Case Focused Experimentation, and two future-state alternative scenarios that may prevail going forward (see Figure 6) .

Figure 6: Current Base Case and Future Alternative Scenarios for FCEV

2021-2025 could be the final policy bonus period for FCEV, given the accelerated commercialization of battery electric vehicle (BEV) propulsion. Parallel investments into hydrogen infrastructure may be challenging in the near term due to existing, on-going commitments made into electrification of road transportation. As such, BEV may receive the self-reinforcing benefits of incumbency previously afforded the internal combustion vehicle era – not the least of which is the legacy of recharging/refuelling infrastructure. If the public and private sector goes “all in” on BEV technology investment including infrastructure, a network effect will squeeze the FCEV into the downside “Hydrogen Fades” scenario.

We believe the upside “Hydrogen Rises” scenario is only possible if China’s City Cluster Policy helps accelerate FCEV adoption initially in the targeted segments highlighted in Figure 4. This can set a foundation for reaching the inflection point of the technology innovation “S-curve”, breaking the trap of high cost and sub-scale deployment.

The City Cluster Policy is promoting FCEV in heavy-duty vehicles that contribute nearly half of China’s greenhouse gas emissions. The ideal entry point will be fixed route applications deployed for institutions with carbon neutral targets, such as green ports, green mines, green steelmaking, among others. In China, these sectors are usually dominated by large SOEs with social and political commitments to follow policy directives, making it easier to implement FCEV demonstration projects targeting specific use cases. If these initial projects help to create a foundation that help drive down system cost, FCEV can scale up in commercial fleet applications where long-range, high-power consumption and low downtime are desired characteristics.

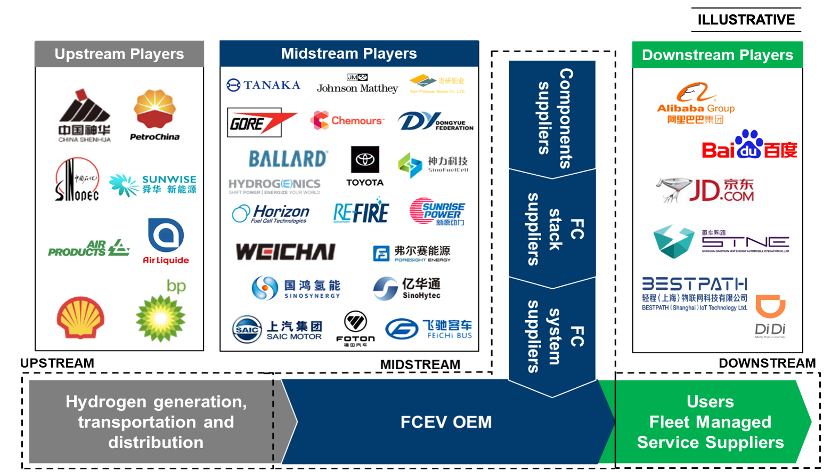

To achieve commercialization, the FCEV value chain (depicted in Figure 7) must evolve to meet the following requirements:

- Reduced Cost (Upstream and Midstream): Achieve scale economies for FCEV key components and systems by aggregation of a sufficient level of capacity thereby lowering system-wide cost

- Technology Innovation (Mid-stream): leveraging the advantages of FCEV to optimize reliability and maximize utilization of vehicles and systems for targeted mobility use cases.

- Available Infrastructure (Upstream and Downstream): Deployment of hydrogen generation and refuelling station capacity that can be operated profitably without subsidy for targeted mobility use cases.

- Targeted Path to Commercialization (Downstream): A clear prioritization of targeted segment coverage, sequenced and weighted according to FCEV’s unique advantages in larger load capacity, longer range and shorter refuelling time.

Source: Desktop research, Automobility analysis

Figure 7. China’s FCEV Value Chain and Landscape

On the midstream FCEV section of the value chain, Chinese domestic companies are improving in their development of core component technologies, but gaps remain for advanced catalyst and Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) technologies. Leading fuel cell system suppliers will seek to vertically integrate core technologies of the fuel cell stack and Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA) through equity investment and JV or other forms of collaboration. Though most Chinese FCEV manufacturers rely on external suppliers for fuel cell related technologies, there is growing emphasis on building in-house capabilities among the domestic players to secure proprietary intellectual property.

Recognizing the potential for China to build the requisite infrastructure and scale the FCEV technology, leading multinational fuel cell system suppliers and manufacturers have entered the Chinese market through direct investments and partnerships. Hyundai Motor Company is spearheading the development of a fuel cell commercial vehicle ecosystem in China with regional partners (see Figure 8).

In October 2020, Hyundai signed a 4-party memorandum of understanding that aims to supply more than 3,000 FC trucks in the Yangtze River Delta area by 2025. Hyundai Motor Hydrogen Fuel Cell System (Guangzhou) is the Group’s first overseas fuel cell system facility, which broke ground in March 2021.

Source: desktop research, Automobility analysis

Figure 8. Hyundai Motor Company’s China FCEV Ecosystem

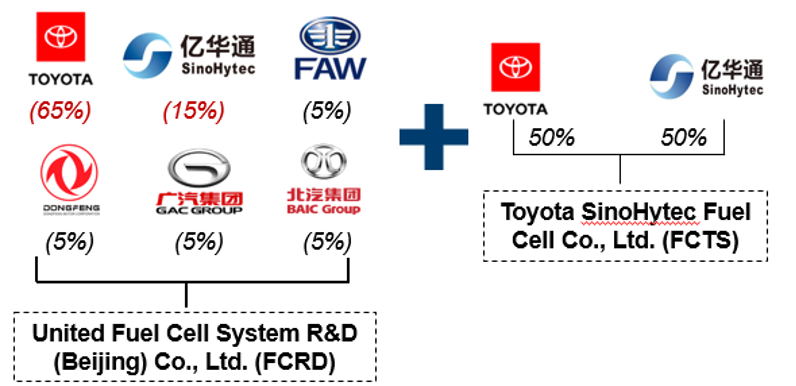

Toyota Motor Company has also formed joint ventures with Chinese partners to develop, produce and sell fuel cell systems for commercial vehicles in China (see Figure 9). In June 2020, Toyota announced a fuel cell R&D joint venture together with FAW, Dongfeng, BAIC, GAC and SinoHytec, named United Fuel Cell System R&D Co. (FCRD). In Mar. 2021, SinoHytec and Toyota Motor officially formed a 50-50 joint venture on the key fuel cell system for commercial vehicles. Both will invest a total of $72.8 million to the new JV.

Source: desktop research, Automobility analysis

Figure 9. Toyota Motor Company’s China FCEV Ecosystem

As China’s policies emphasize building a strong domestic value chain, these examples demonstrate that foreign FCEV players can position themselves as upstream and midstream tech ecosystem partners at the current stage. This does not exclude the potential for them to play an expanded role when the market reaches commercial scale , as Tesla has demonstrated with their approach to BEV in China.

In this article, we have emphasized the critical importance of government policy in steering FCEV development. We believe this is the critical point that differentiates China: a massive ability to mass-commercialize mobility solutions and a unique ability to leverage public and private partnerships (PPP) to drive commercialization of high-tech innovation. On the path to mass commercialization of mobility technology, the key question is always “when do we expect large private sector investments to kick in?”.

In our view, PPP will help de-risk investments in the Hydrogen and FCEV sector. It is also important to understand that China’s commitment to this sector is a key part of the broader campaign to control the upstream supply chain of technology needed to power sustainable economic development. Global companies will need to form partnerships to play a role in the Hydrogen and FCEV development in China. It is important to form such partnerships now with the local ecosystems that are targeting commercial vehicle use cases in the segments most likely to embrace the technology.

_____________________________________________________________________

About Automobility

Automobility Limited is global Strategy & Investment Advisory firm based in Shanghai that is focused on helping its clients to Build and Profit from the Future of Mobility. We help our clients address and solve their toughest business and management issues that arise in midst of fast changing, complicated and ambiguous operating environment. We commit to helping our clients to not only “design” the solutions but also raise or deploy capital and we can assist in implementation, often together with our clients. We put our clients’ interest first and foremost. We are objective and don’t view our client engagements as “projects”; rather as long-term relationships.

Our partners are former senior executives at large corporations and/or senior consultants at leading management consulting firms. We believe clients would benefit the most from a combination of consultants with substantive experience in consulting and in line management.

Therefore, we organize ourselves into a core team augmented by an extensive “extended team members” with a large variety of skills and expertise.

_____________________________________________________________________

Automobility EXCELerrate Pipeline – Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Tech Startups

Automobility provides investment advisory, merchant banking and business development services for investors, corporations, and startups. Our startup portfolio is curated based on fit and relevancy to our thesis on the future of mobility, with a particular emphasis on markets with a high potential to commercialize their technology.

Startups in our pipeline in the Hydrogen and Fuel Cell category include:

Mpower Innovation is making continuous and breakthrough improvement in hydrogen and fuel cell technologies, accelerating the way towards green hydrogen society and a net-zero emission future.

Bartini is an aviation and engineering company that develops a fuel cell electric powered vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) for private use and emerging urban air taxi.

Please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected] if you would like further information on these startups or to learn more about other Auto & Mobility investment opportunities from our EXCELerate opportunity pipeline.

_____________________________________________________________________

About the Authors

Bill Russo is the Founder and CEO of Automobility Limited. His over 35 years of experience includes 15 years as an automotive executive with Chrysler, including 17 years of experience in China and Asia. He has also worked nearly 12 years in the electronics and information technology industries with IBM and Harman. He has worked as an advisor and consultant for numerous multinational and local Chinese firms in the formulation and implementation of their global market and product strategies. Bill is also currently serving as the Chair of the Automotive Committee at the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai.

Contact Bill by email at [email protected]

Emily Wang is an Associate of Automobility Limited. She has 11 years of experience in Management Consulting and Marketing in Greater China and U.S., spanning over multiple consumer and industrial sectors. She is knowledgeable about China’s mobility market, technology innovations and digital ecosystem. She has helped multinational, Chinese POE and SOE and startup clients developing strategy for new market entry, M&A pipeline, due diligence, organization structure and operating model design etc.

Contact Emily by email at [email protected]

Maggie Zhou is an project consultant of Automobility Limited. She had 14 years of energy and resources industry experience in Australia, Singapore, Greater China, Africa and UK. She has diverse commodity exposure including Metals, Iron Ore, Metallurgical Coal, Energy Coal and Petroleum. Her diversified functional experience across corporate strategy and planning, management consulting, marketing, project management and finance.

Contact Maggie by email at [email protected]

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.