19 Jun China’s New Energy Car Quest

The Wire China, June 14, 2020

The electric vehicle company NIO was about to crash, but many think Beijing, intent on dominating the industry, grabbed the wheel.

Last December, the electric vehicle company NIO hosted its annual celebration for customers in Shenzhen, one of China’s entrepreneurial hotbeds. The event, called “NIO Day,” mixes an Apple-style keynote address with the lighting and theatrics of a stadium concert. Among the evening’s highlights was a musical skit by the Blue Sky Chorus, a troupe of volunteer performers who are all NIO customers.

In original lyrics they composed, the group catalogued their heartaches through the company’s tumultuous journey — “old classmates snickered, the whole neighborhood gossiped” — then broke into a rap sequence where they fired back. The second verse described the joys of driving a NIO car and their commitment to the company’s success.

They sang: “The NIO life is worth loving with all your spirit. If I can choose again, I would still choose NIO.”

Sitting in the front row, watching intently, was William Li, the 45-year-old founder and chief executive of NIO. In company promotions, NIO’s Chinese name, Weilai, is translated to mean “blue sky coming.” But heading into this year, the forecasts were grim. The company had been racked by mounting losses, battery recalls and a wave of layoffs. Its shares, traded on the New York Stock Exchange, had plummeted more than 60 percent off their high.

Wall Street analysts were openly questioning how long the company would survive.

When he took to the stage, Li appeared reflective. “NIO has faced many challenges,” he said. His voice was breaking, “It is only because of you that we have made it to this day.” He took a breath and bowed.

It was a dramatic turn of events. Founded in 2014, NIO had been built on a radical idea: a Chinese startup would produce fast cars with cool designs for the high end electric vehicles dominated by Elon Musk’s Tesla. And it would achieve this without a single factory, contracting the manufacturing out to local partners, allowing NIO to focus on designs, technology and the all important “user experience.”

In California, another brash Chinese entrepreneur named Jia Yueting (see The Wireprofile) was spending billions of dollars to build another high end electric vehicle maker, called Faraday Future, in Tesla’s own backyard. Li, the serial entrepreneur behind NIO, would stake his claim inside China. Determined to catch Tesla, he founded the company with Martin Leach, a legendary race car driver and former Ford executive, with the aim of selling a home-grown luxury SUV called the ES8, priced at $65,000.

His vision was backed by an all-star roster of global investors, Chinese technology giants and Wall Street bankers, including Tencent, Baidu, Hillhouse Capital, Sequoia Capital and Goldman Sachs.

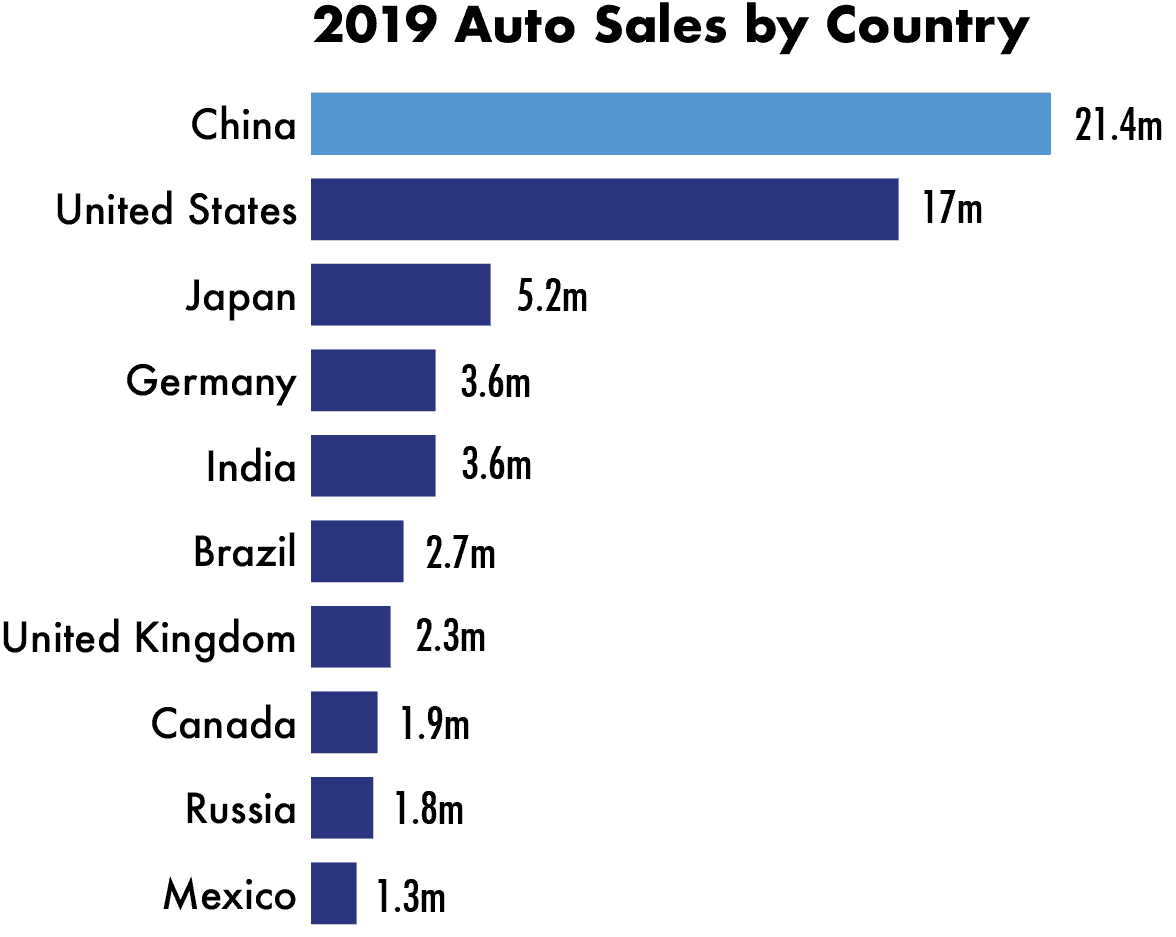

They had reason to be optimistic. China is the world’s largest auto market and also the world’s largest market for electric vehicles. And yet the country’s car market is still dominated by foreign joint ventures backed by the likes of Ford, Volkswagen and General Motors — something that gnaws at Beijing’s eagerness to build up China’s own capabilities.

As a result, the Chinese government has spent more than $60 billion (mostly through subsidies) to make China a leader in electric vehicles, and it is committed to spending much more. The goal is partly aimed at cutting the nation’s reliance on oil imports and reducing pollution, but also to jumpstart the shift toward so-called EVs so that domestic firms might leapfrog foreign producers.

After all, Japan has Toyota and Honda; South Korea has Hyundai and Kia. Could China create its own industry leading automakers in EVs?

Fast-tracked by Beijing’s policies, electric vehicles sales topped 1.2 million in 2018. McKinsey, the consulting firm, forecasts sales of 5 million electric vehicles in China by 2024.

“The Chinese government has decided, ‘We have to be innovators,’” said Michael Dunne, chief executive at the consulting firm Zozo Go. “Electric propulsion presented a once-in-a-generation opportunity.”

Li, who in China is known as Li Bin, jumped into the race by forming an electric vehicle company initially named NextCar. He recruited executives from Tesla, BMW and Lexus, opened offices in Europe and the U.S., and by 2017 claimed to have the world’s fastest EV (clocking speeds of nearly 200 miles per hour). Then he listed his startup on the New York Stock Exchange in 2018. No other automaker has made a speedier leap from idea to American I.P.O.

Along the way, he has raised $7 billion.

Now, just two years after its initial public offering, NIO is deeply in debt, and people are questioning whether it moved too quickly. The company failed to deliver on sales, even as it expanded by building NIO houses and luxury lounges to cater to its customers, splurging on premium leather seats and developing its own dashboard-affixed robot, called NOMI.

Shareholders have seen the company’s value rocket up to nearly $12 billion after the I.P.O., only to fall back to earth. Today, NIO is valued at about $6.5 billion.

In February, with auto sales in free fall during the pandemic, Chinese government officials in Hefei, the capital of Anhui Province, offered a lifeline: in exchange for an infusion of $1 billion in cash, the government would take a 24.1 percent stake in a new joint entity called NIO China.

Why, some are asking, would the government bail out a private firm that was initially backed by some of the world’s biggest internet companies?

PEDAL TO THE EV METAL

Until the 1990s, China had more than a billion people but virtually no market for passenger cars. To stimulate domestic development, the government’s early directives were based on a simple formulation: entice foreign auto makers to set up joint ventures with Chinese state-run vehicle manufacturers. Over time, the hope was that China would acquire the know-how and technological capability to build its own globally competitive fleets.

One of the earliest efforts rolled out in 1982, when Volkswagen set up a joint venture with the Shanghai Tractor and Automobile Corp. to build engines and cars, mostly for government officials and businesses. (At the time, the bicycle was still the main mode of transportation for ordinary people in Chinese cities.)

In hindsight, the early deals may have backfired. On the one hand, they granted foreign automakers like GM and Volkswagen a foothold in China; on the other, Chinese state car makers had a near monopoly, since many deals were regional. Each side profited from the phenomenal growth of China’s economy and surging demand for cars.

But the joint ventures also stifled competition, analysts say, preventing China from developing its own competitive car makers. Domestic producers came to rely on the standards and expertise of their global partners; foreign models soon controlled nearly every segment of the passenger vehicle market. Among luxury cars, independent, privately owned Chinese brands were nearly nonexistent.

“The Chinese auto industry got big,” said Rupert Mitchell, the chief strategy officer at WM-Motor, “but it didn’t get strong.”

The electric vehicle market promises to change that. EVs can be made from fewer and less exacting parts and require lighter infrastructure; in some ways, they have as much in common with combustion engines as the Model T did with horses. From behind the curtain, Beijing’s central planners seized on another chance.

In 2010, the government designated “new-energy vehicles” (NEVs) as one of its seven “strategic emerging industries.” The broad shift toward electric would give Chinese carmakers the opportunity to excel commercially in ways they had never managed with the internal combustion engine.

“The whole point of EV vehicles was to reboot the Chinese auto industry,” said Hui He, the China regional director of the International Council on Clean Transportation.

Building EVs would require new ideas, huge amounts of capital and ambitious entrepreneurs. And that’s where William Li fits in.

Born in Anhui Province, in one of the country’s poorest regions, Li managed to gain admission to an elite school, Peking University, in Beijing. He then flexed his entrepreneurial muscle by working at a string of ecommerce startups, including what eventually became the online bookseller Dangdang.

He also founded a series of startups centered on his passion for marketing and automobiles. He set up an online car seller in 2000 called Bitauto, which was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 2010; formed a Beijing advertising firm (2002); Yixin (2014), a car financing company that was a Bitauto spinoff and later listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. And even after founding NIO (2014), he set up one of China’s biggest bike sharing startups, called Mobike (2015). That startup was sold for about $2.7 billion to the ecommerce giant Meituan, according to Reuters, after the market for bikes got saturated.

What is perhaps most striking about Li’s career is the collection of powerful backers who have trailed behind him, investing huge sums, again and again, in his ventures: Baidu, Tencent, JD.com and Temasek, even one of China’s best-known serial entrepreneurs, Lei Jun, who co-founded the mobile phone startup Xiaomi.

While the performance of his companies has been mixed, he has done something few other entrepreneurs can boast: he has successively listed three public companies, on exchanges in Hong Kong and New York. That may help explain why an EV startup run by an entrepreneur with no engineering experience managed to raise about $7 billion over the past six years.

His entrance was well timed. In 2015, a year after NIO was founded, Chinese premier Li Keqiang further elevated the industry when he announced electric vehicles would be a key pillar in his administration’s Made in China 2025 industrial plan.

A wide array of policy tools were mobilized to help domestic producers meet the goal: research funding, emissions guidelines, import tariffs, purchase subsidies, tax exemptions, license restrictions, and more. Boosted by the many firing pistons of state support, China today has the world’s biggest market for electric vehicles — greater than the U.S. and Europe combined.

“The market is entirely a creation of Chinese state policy,” said Scott Kennedy, a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. According to his research, the government has spent more than $60 billion to foster and promote the industry — almost half the sector’s entire commercial activity.

The Chinese EV sector, Kennedy said, “would not exist without a clear overall goal, and strategies to support that goal.”

Eager to make the most of these tools, NIO decided to focus on the consumer experience. Li is steeped in the mythos of growth, innovation and design, and NIO burst from the starting line intent on achieving the gold standard in everything — from the car’s lightweight frames to its autonomous driving software and artificial intelligence features to its eponymous lifestyle brand.

The “global startup” opened offices in twelve major cities, with its main headquarters in Shanghai. NIO promised a consumer model for the U.S. market by 2020.

In 2018, the company unveiled its first passenger vehicle, the ES8, which at $65,000 — was priced significantly lower than Tesla’s Model X. NIO’s signature invention is NOMI, an artificial intelligence robot fixed to the dashboard of each vehicle.

The robot’s name is an amalgamation of “know me,” a kind of pledge to customers. NOMI navigates directions, cues music, scouts the weather, and adjusts seat settings and cabin temperature according to user preferences. Coded with nearly 100 emojis, NOMI can smile and wink, flaunt delight or pout confusion. Aided by sensors, it swivels to address whoever is speaking. It even takes selfies of passengers on command.

Izzy Zhu, NIO’s former head of user development, said this attention to emotional details set NIO apart from Tesla.

“Tesla is very geeky. It has very cool technologies,” Zhu told The Wire earlier this year, before leaving the company in March. “But the company doesn’t care too much about the user’s feelings.”

Li’s stated goal for NIO is not just to build cars, but usher in a new lifestyle.

“If you want to redefine the industry,” he told an audience in 2018, “you must redefine the user experience of the industry.”

To this end, NIO outsources its manufacturing to a state-owned factory called Jianghuai Auto so that the company can focus on the “user experience.”

“They don’t even make the hardware,” said Bill Russo, a former executive of Chrysler China and the Founder and CEO of Automobility Ltd. “The device is used to attract users into its platform” like the way Amazon uses the Kindle reader and Echo smart speaker.

Flush with capital, NIO sought to create an ecosystem for users to nest in, starting with the NIO app that grants its customers access to elegant club houses all over China. In one of Shanghai’s three “NIO Houses” earlier this year, NIO Life products on display included everything from water bottles to polo shirts and sneakers. Members could pay with cash or NIO points. On one wall, a flat screen panel displayed the week’s schedule, including calligraphy lessons and an essential oils workshop. The in-house café promoted the season’s NIO-themed specialty drink: “Shine on Blue,” a frothy latte made with blueberries.

‘THE NIO RULE’

By late 2019, the repercussions of NIO’s relentless pace and spending were beginning to show. In its early deliveries of the ES8, bugs in the car’s software prompted a lousy user experience, dampening referrals and sales. A few months later, batteries in several ES8s caught fire, prompting a recall. Sales targets were missed repeatedly, even as the company’s swanky clubhouses and services grew costly.

Zhu, the former head of user development, said people often lose sight of how young the company is, and compared it to a five-year-old. “We were on a racetrack, and we had to grow up so fast,” he said, admitting the company made mistakes.

After years of aggressive hiring, the company began scaling back as early as March of 2019, reducing its workforce by 25 percent, to about 7,500 employees.

Rivals also emerged. Stirred by years of generous state handouts and exemptions, the Chinese electric vehicle sector was sagging with overcapacity, with scores of vehicles clamoring for market share. One analyst likened the bloated sector to the “Warring States Period” — harking back to the era of chaos and conquest that blotted China’s pre-modern history.

NIO was just one of many swaggering entrants. Nanjing-based Byton, for example, recruited its top ranks from Apple and Google, while Xpeng Motors gave away its first 400 cars as a “beta test” to collect feedback from drivers. The sector’s most promising startups shared a common inheritance: big investment stakes by China’s prominent tech giants.

“All of these companies have digital DNA,” said Russo, the former Chrysler China executive. “They were all invested by a Tencent or an Alibaba at some point.”

Fearing overcapacity, the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s national economic planning agency, enacted measures in January 2019 to “strictly control” the production of new EVs. To reign in the bloat, the government eventually slashed more than 70 percent of the subsidies through 2019. “The only thing keeping the EV market growing was subsidies,” said Tu Le, the founder of Sino Auto Insights.

By October, NIO’s stock price had plunged about 90 percent from its high. Online commentators took to describing NIO investors as “garlic chives” — Chinese shorthand for naive investors whose bets quickly sour. In the fourth quarter of 2019, Hillhouse Capital, one of NIO’s earliest major backers, sold its remaining stake.

Meanwhile, assessments of the sector’s environmental impact were mixed at best, with critics arguing there was little evidence of reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The troubles compounded a broad slowdown across the industry, fanned in part by tensions over the trade war. China’s auto market shrank for the first time in 30 years.

“We know about NIO and BYD,” Greg Anderson, author of Designated Drivers: How China Plans to Dominate the Global Auto Industry (2012), said of the government policy fallout, “but what about all these companies that didn’t make it? A lot of them we don’t even know their names because they bloomed and wilted immediately.” To survive, he said, “you have to do something to make noise.”

NIO’s ramp appeared to be running out. In February, as China’s economy shut down during the pandemic, the company was so strapped for cash that Li told staffers that their salaries would be delayed.

Then, before the end of the month, government officials in Hefei, the capital of Anhui province, stepped in to extend what would become a $1 billion cash infusion. On a Tuesday morning, the two sides gathered for a signing ceremony to approve the paperwork. Everyone wore a face mask. Behind them, large characters covered a wall that read: “Hefei City Heavy Industrial Projects Centralized Signing Ceremony.”

Robin Zhu, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein, called the deal a bailout. The transaction, he said in a note, “puts speculation around NIO’s funding issues to bed — at least in the foreseeable future.”

A key condition in the agreement was for the electric vehicle producer to establish a major presence in Hefei. Previously, the company had divided operations: its headquarters in Shanghai oversaw manufacturing; a regional hub in Munich led vehicle design; and an office in San Jose, which was considered the startup’s “brain.” NIO China, however, was required to transfer many of the company’s core functions, from research and development to sales and manufacturing operations to the new location in Hefei.

Such terms were seen as crucial for securing local investment, and now the Hefei investor group — consisting mostly of state-owned construction and investment firms — owns 24 percent of NIO China, a subsidiary of NIO Inc., the holding company listed in New York Stock Exchange. NIO Inc. owns the other 76 percent.

Jeremy Raper, founder of independent research service Raper Capital, has called the new arrangement with NIO China an “asset strip, plain and simple.” (Raper said he has made an investment betting the share price will fall.)

But many analysts — including those at Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and Merrill Lynch — have “upgraded” their valuations of NIO stock as a result of the cash infusion and stronger than expected first quarter sales.

NIO’s prospects are also being aided by reinforcements for China’s EV sector from the central government. This spring, Prime Minister Li Keqiang delivered a government work report that emphasized China’s commitment to emerging technologies.

“First, we will step up the construction of new types of infrastructure,” he said, adding: “We will build more charging facilities and promote wider use of new-energy automobiles. We will stimulate new consumer demand and promote industrial upgrading.”

Then, in April, the country’s finance ministry said it would extend purchase subsidies and tax exemptions through 2022. But the subsidies would only apply to passenger cars that sell for less than 300,000 RMB (or about $42,000), shutting out EV offerings from premium brands — notably Tesla’s Model 3. (Shortly after the announcement, Tesla lowered the price of its Model 3 to qualify.) Though both of NIO’s passenger models were priced above the cutoff, Beijing also announced an exemption for EVs with swappable batteries — a carveout that many viewed as favoring NIO.

It’s a sign, analysts say, that whether the EV industry is bloated or not, China is determined to drive the future of the electric vehicle. Le, founder of Sino Auto, called it “the NIO rule.”

Samuel Sharpe contributed research for this article.

Click here to read the article at The Wire China

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.